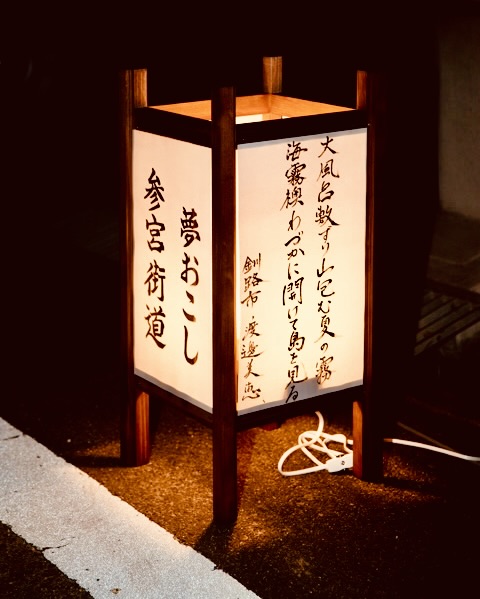

文学と神楽坂

芳賀善次郎氏の『新宿の散歩道』(三交社、1972年)「牛込地区 4.繁華街の核、毘沙門様」を見てみましょう。ここでは、主に参考書『郷土玩具大成』の中の“七福神”を扱います。つまり、8種(谷中、向島、芝、亀戸、東海、麻布稲荷、山の手、柴又)の七福神です。

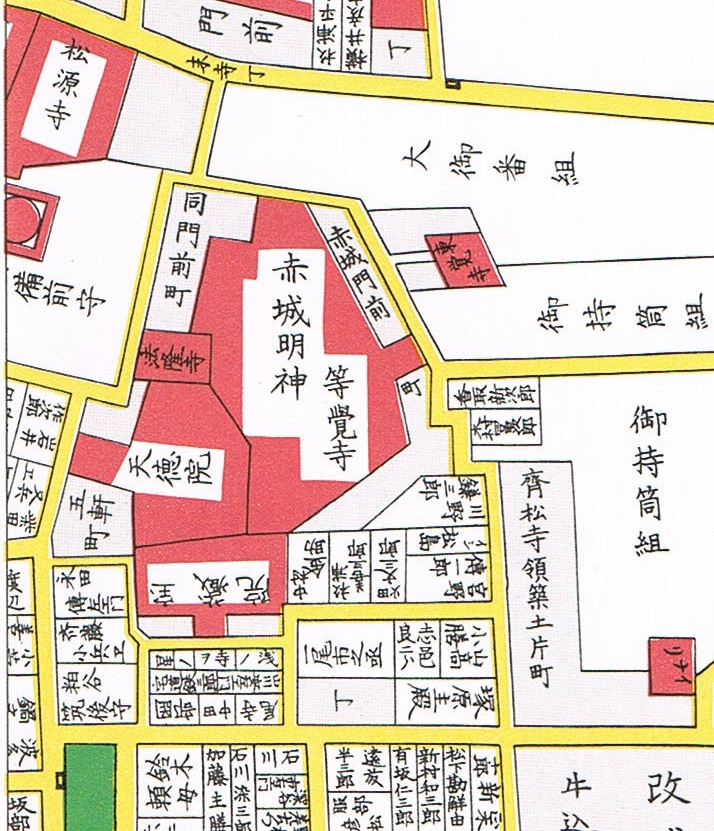

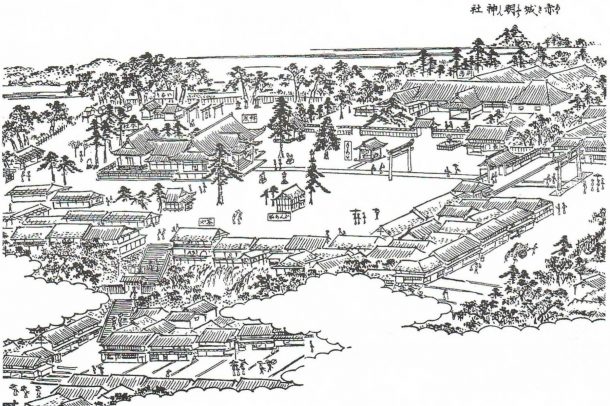

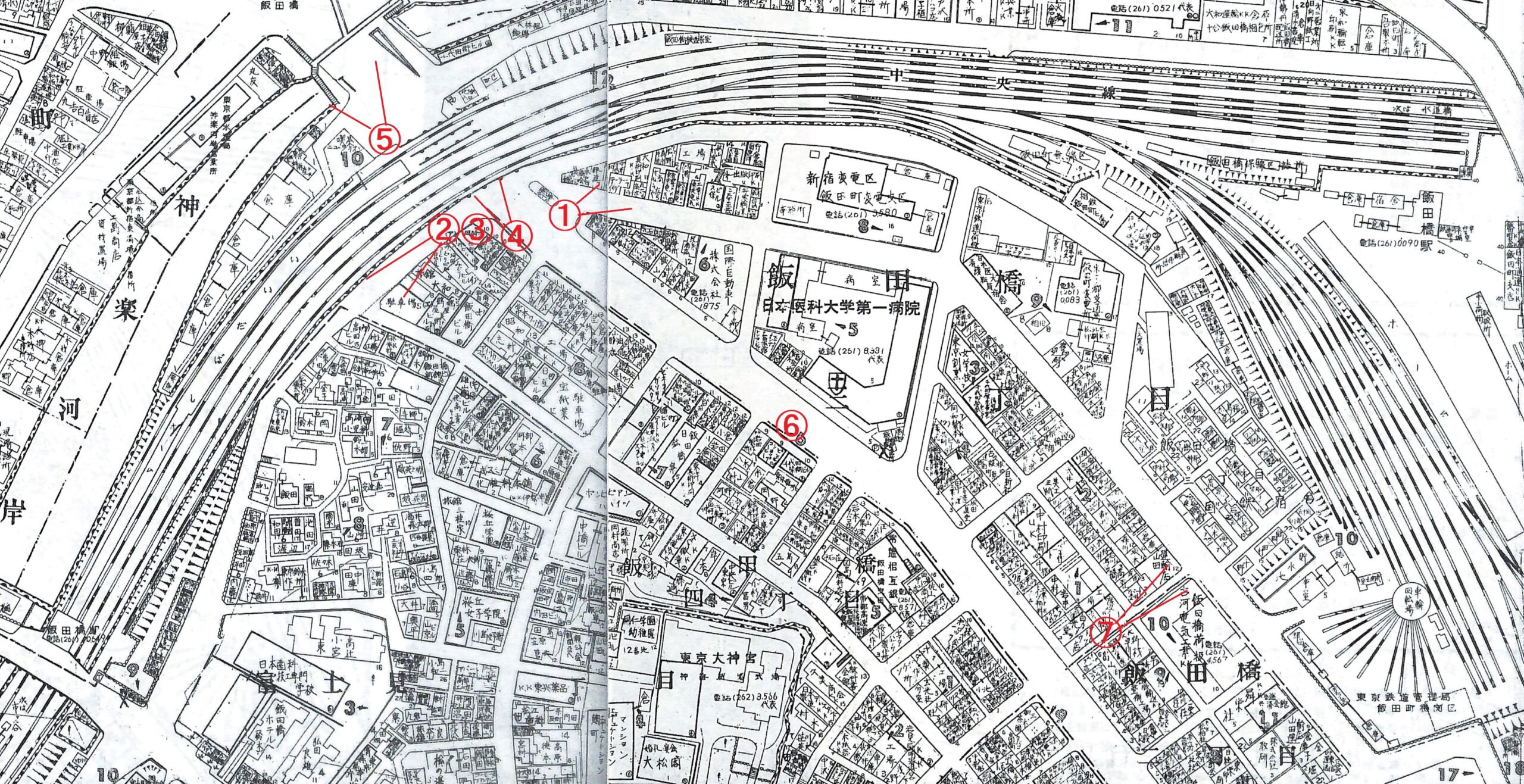

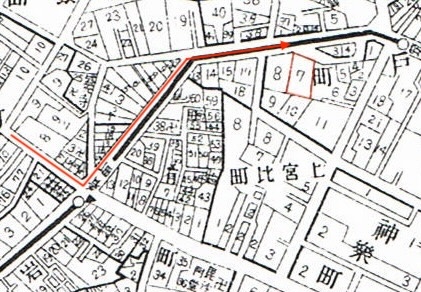

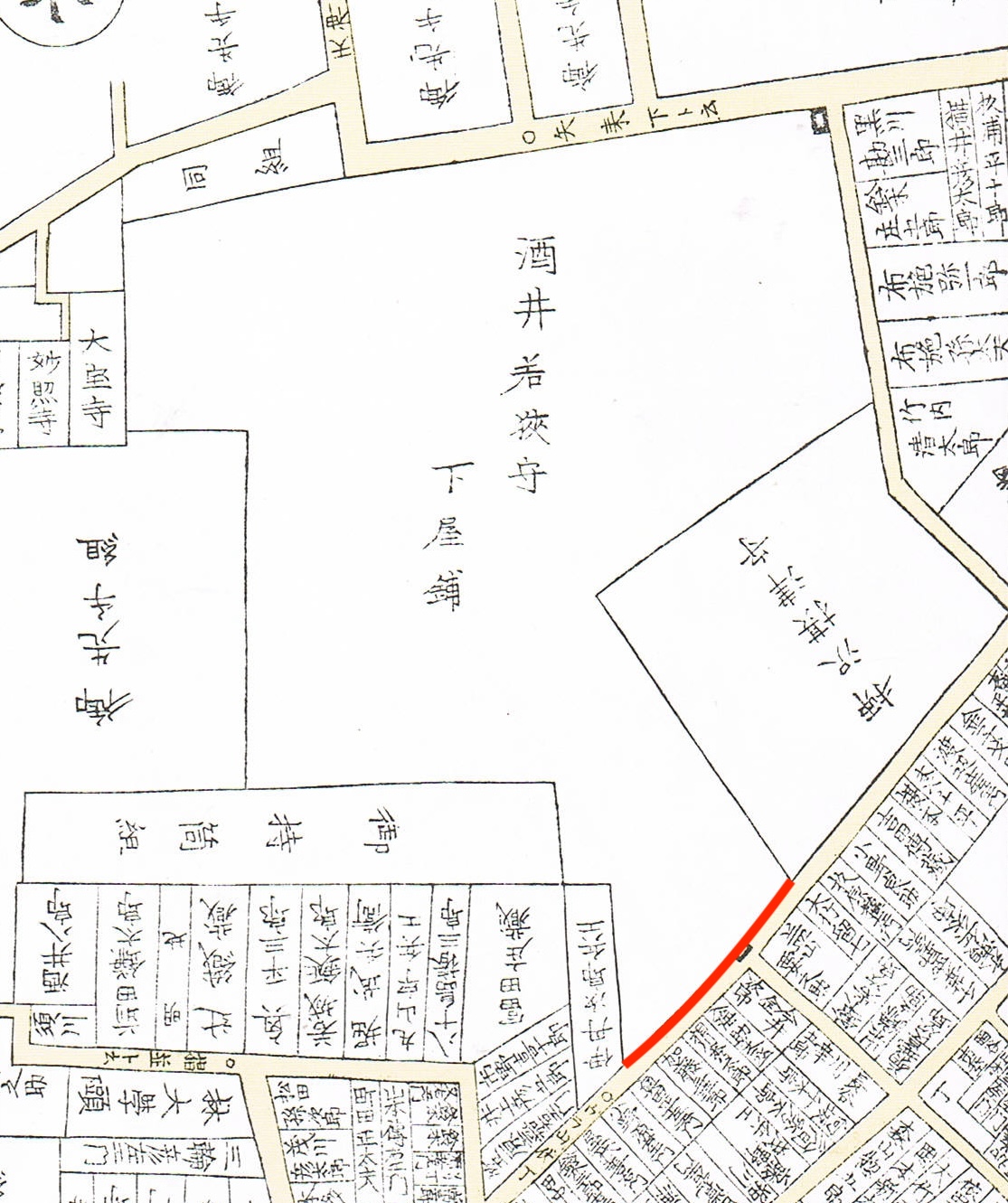

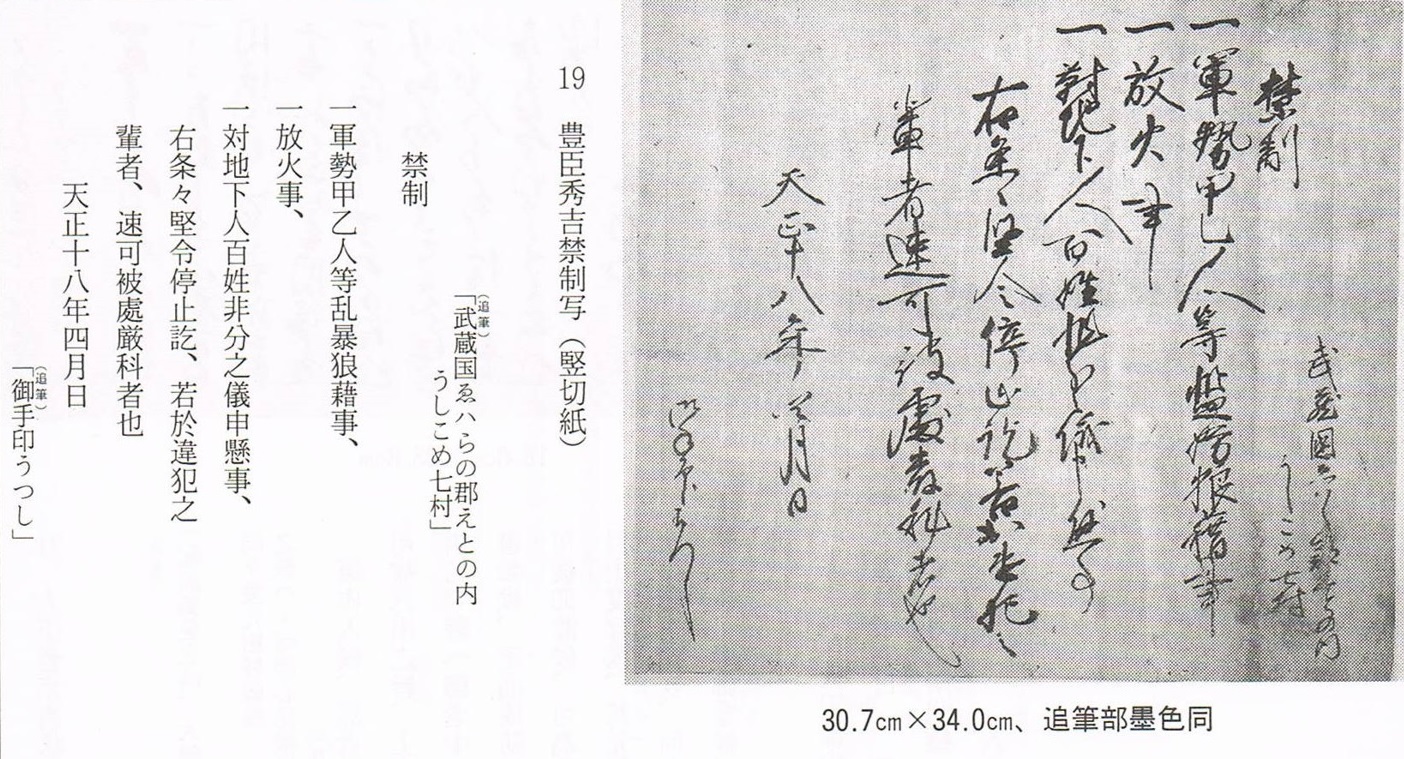

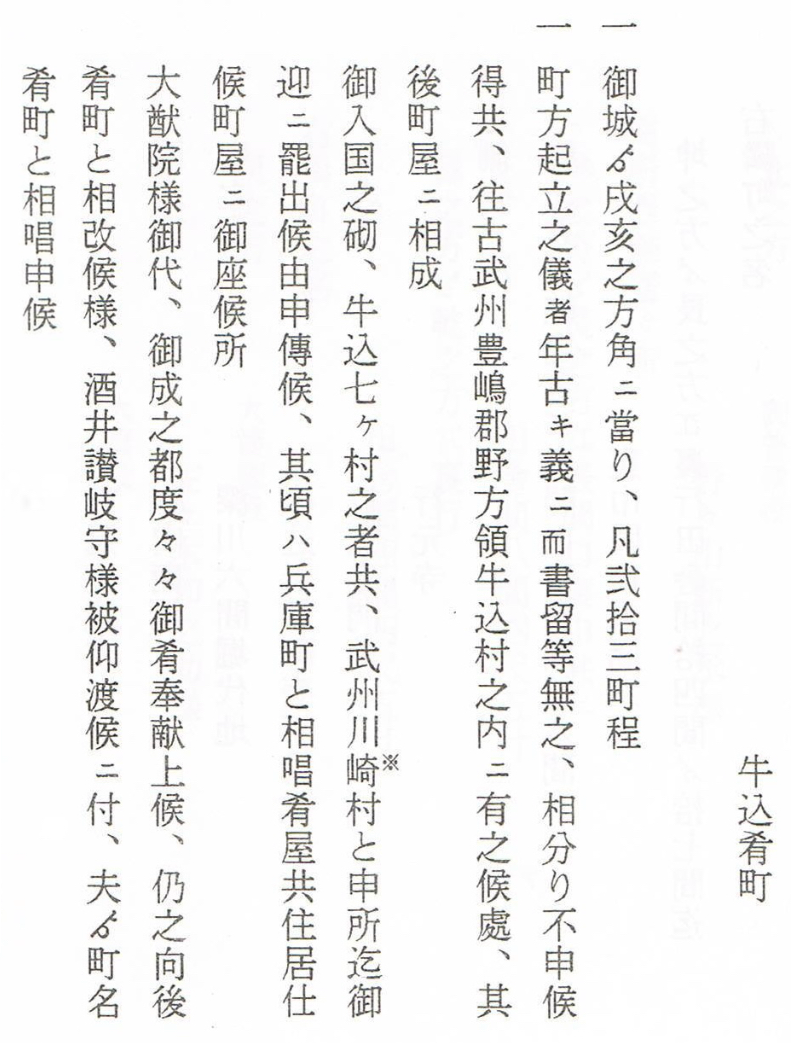

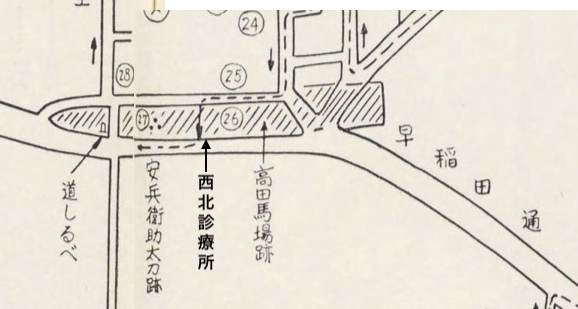

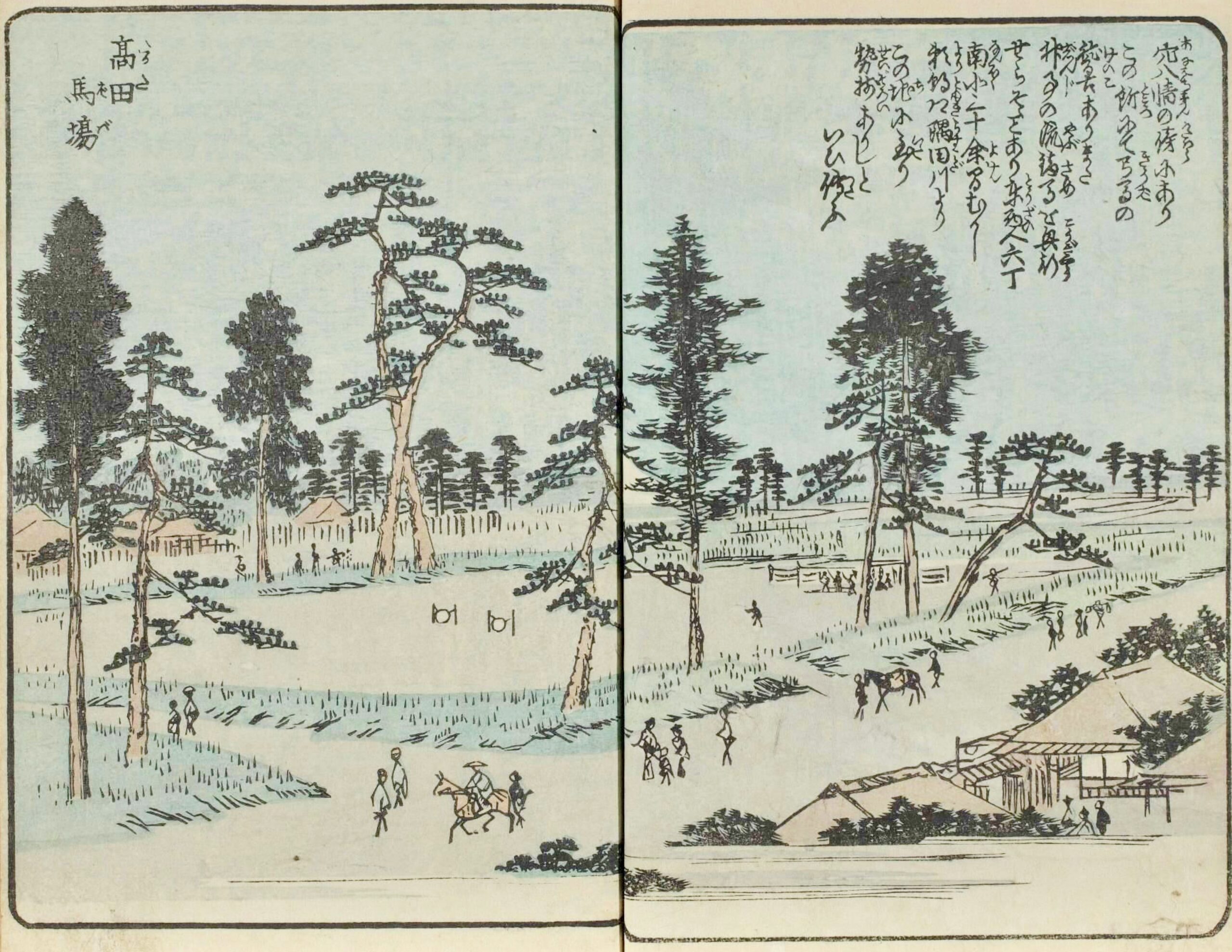

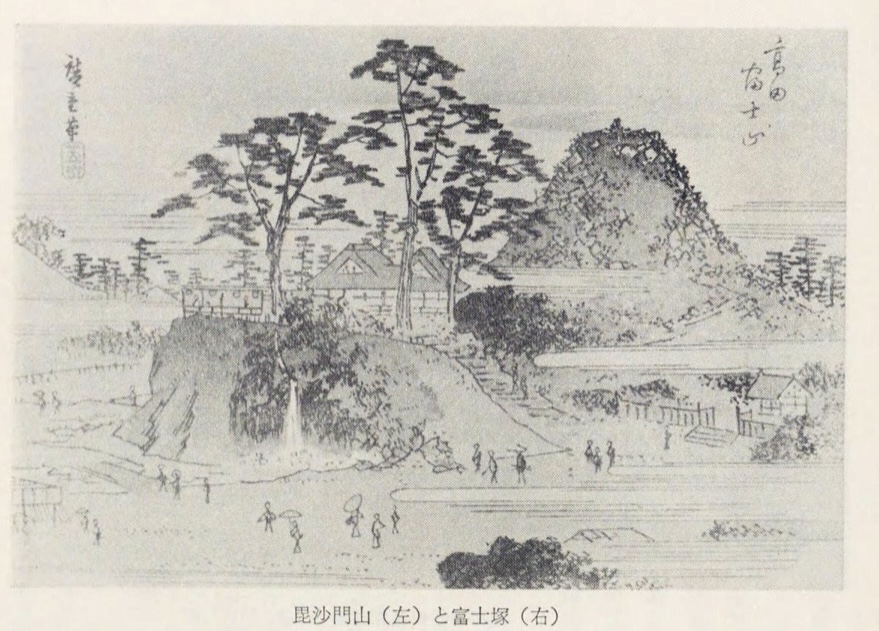

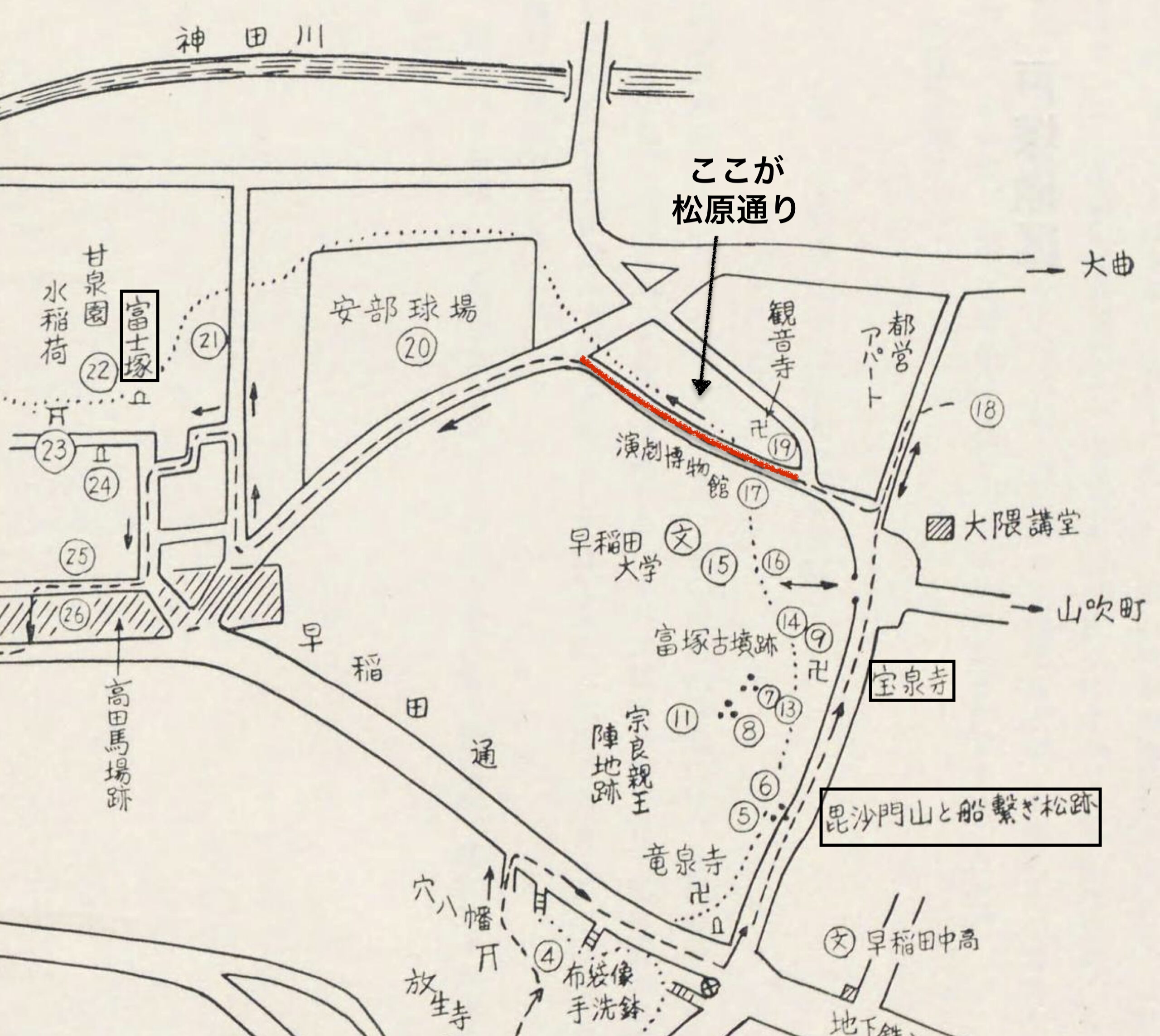

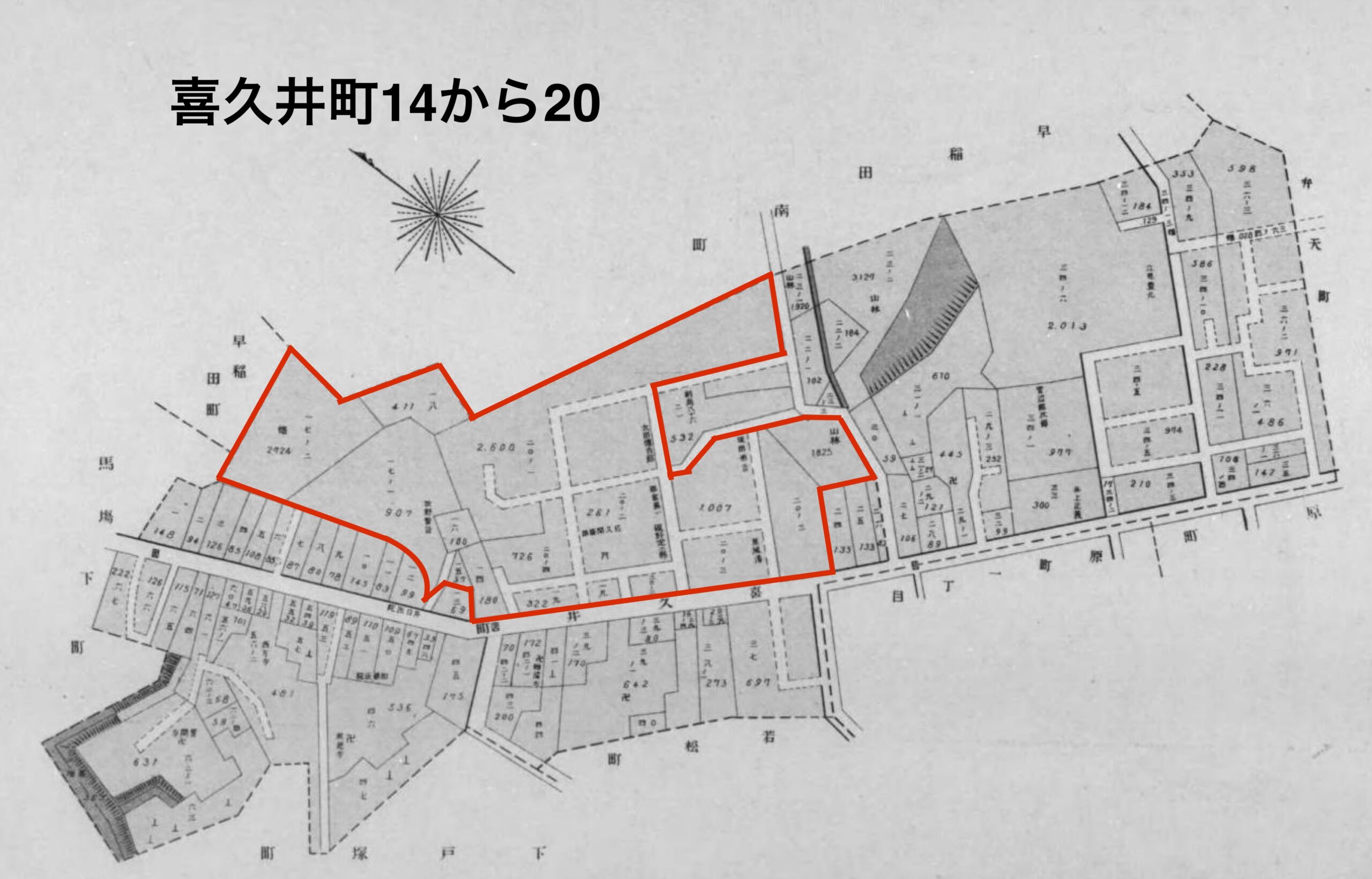

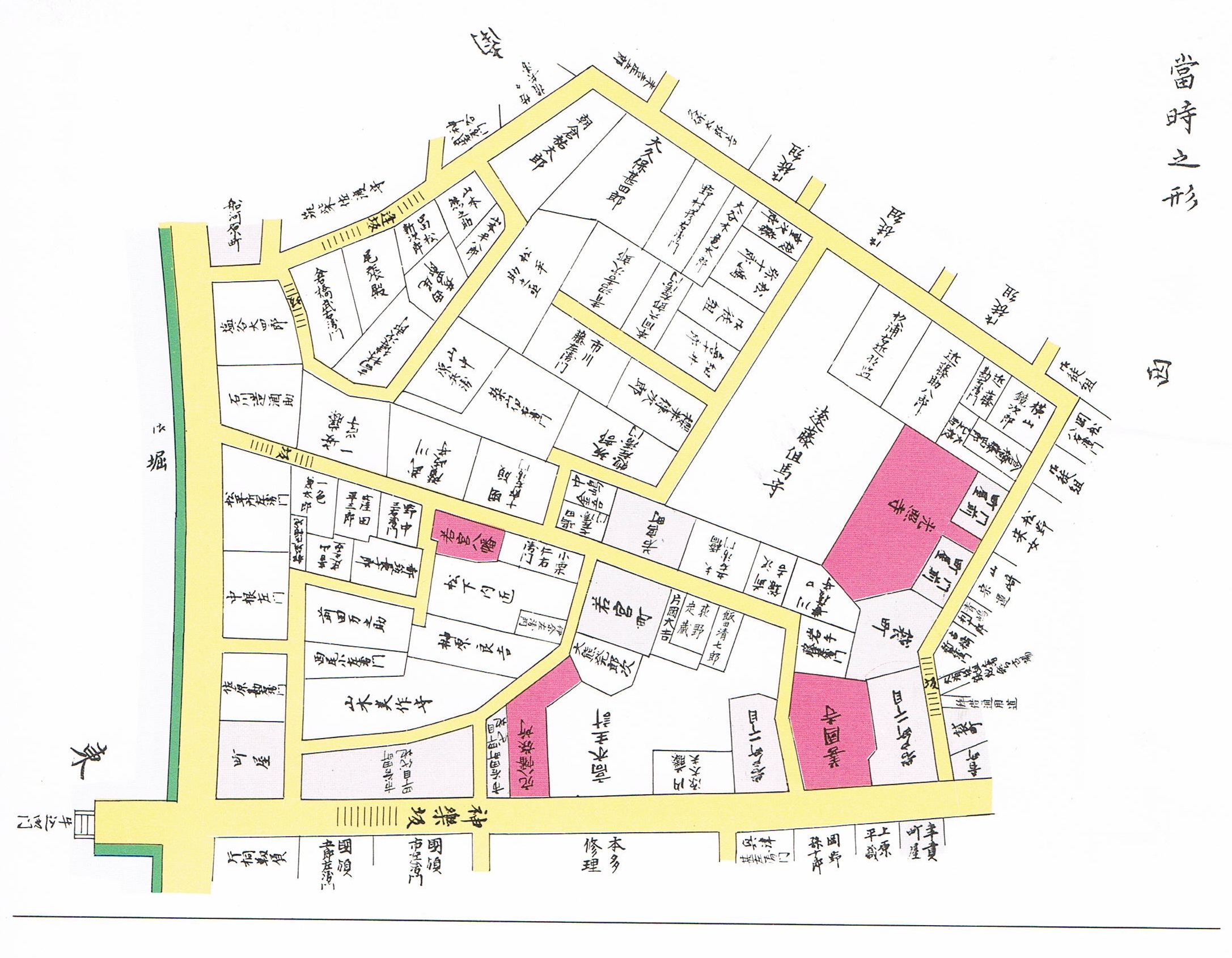

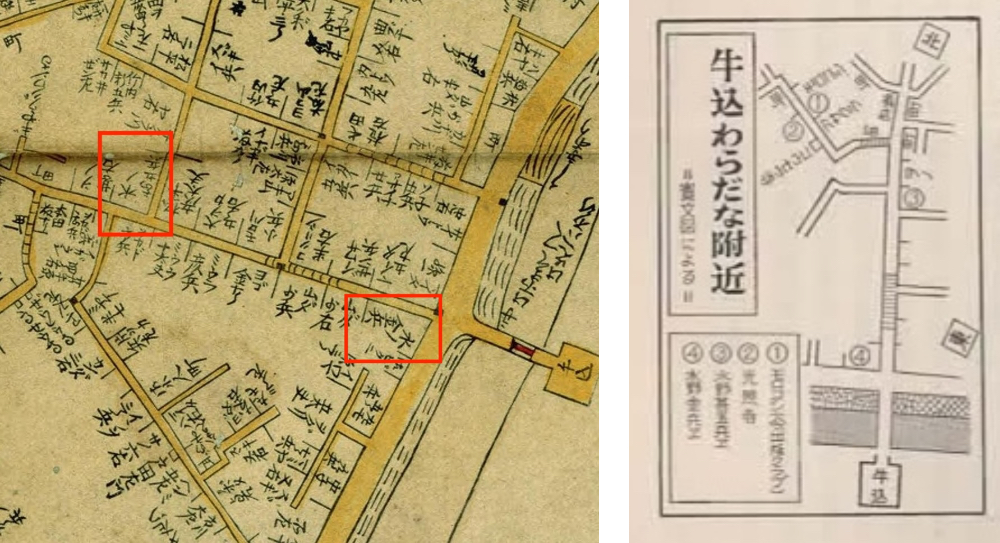

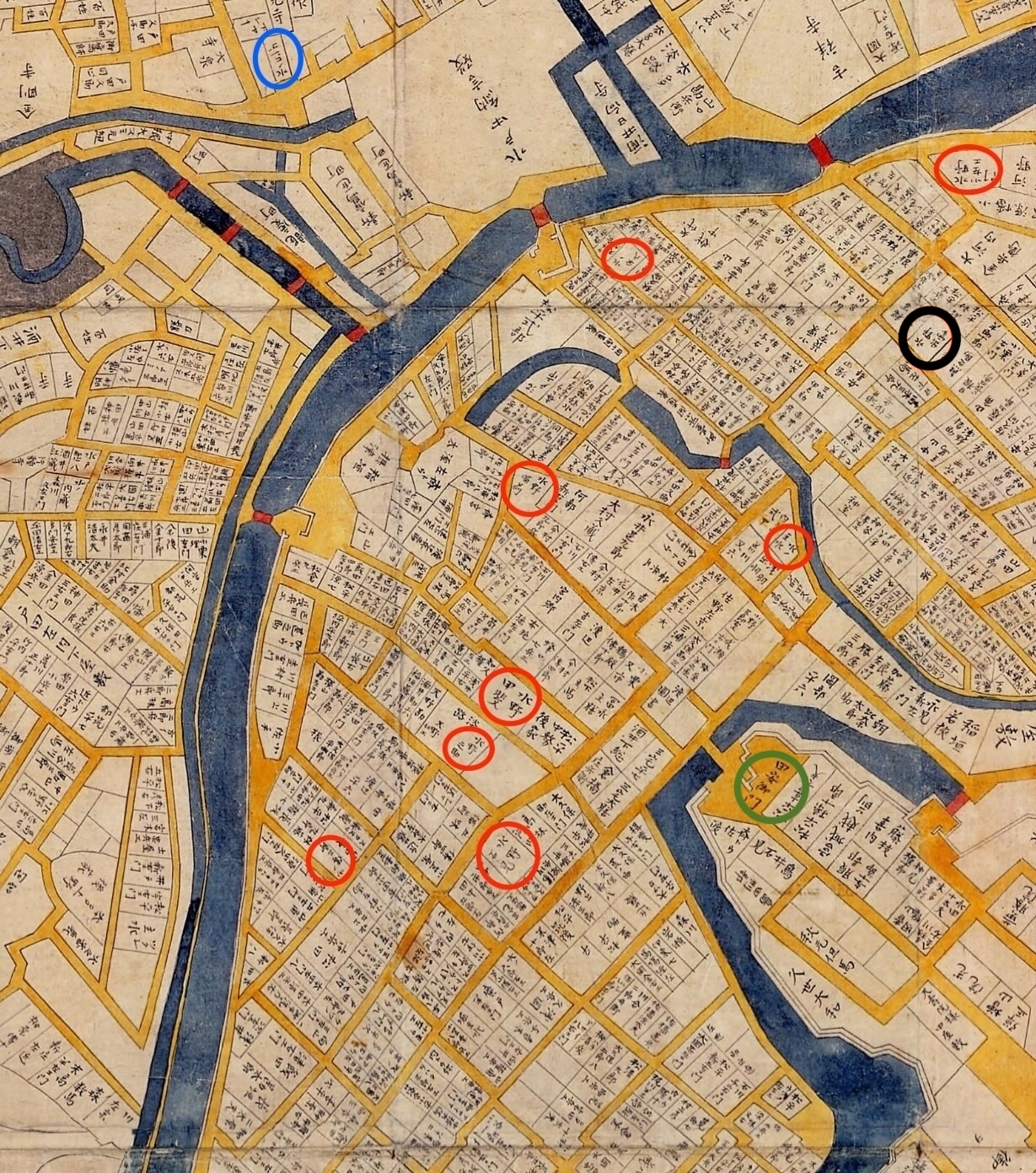

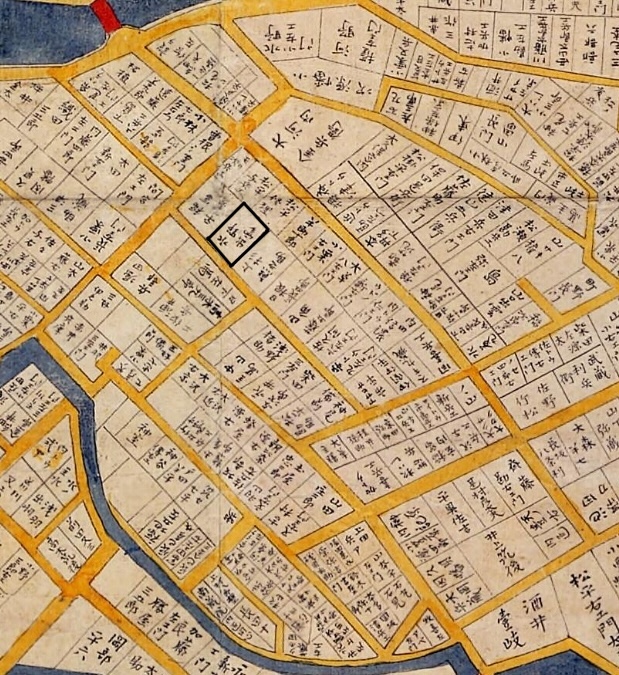

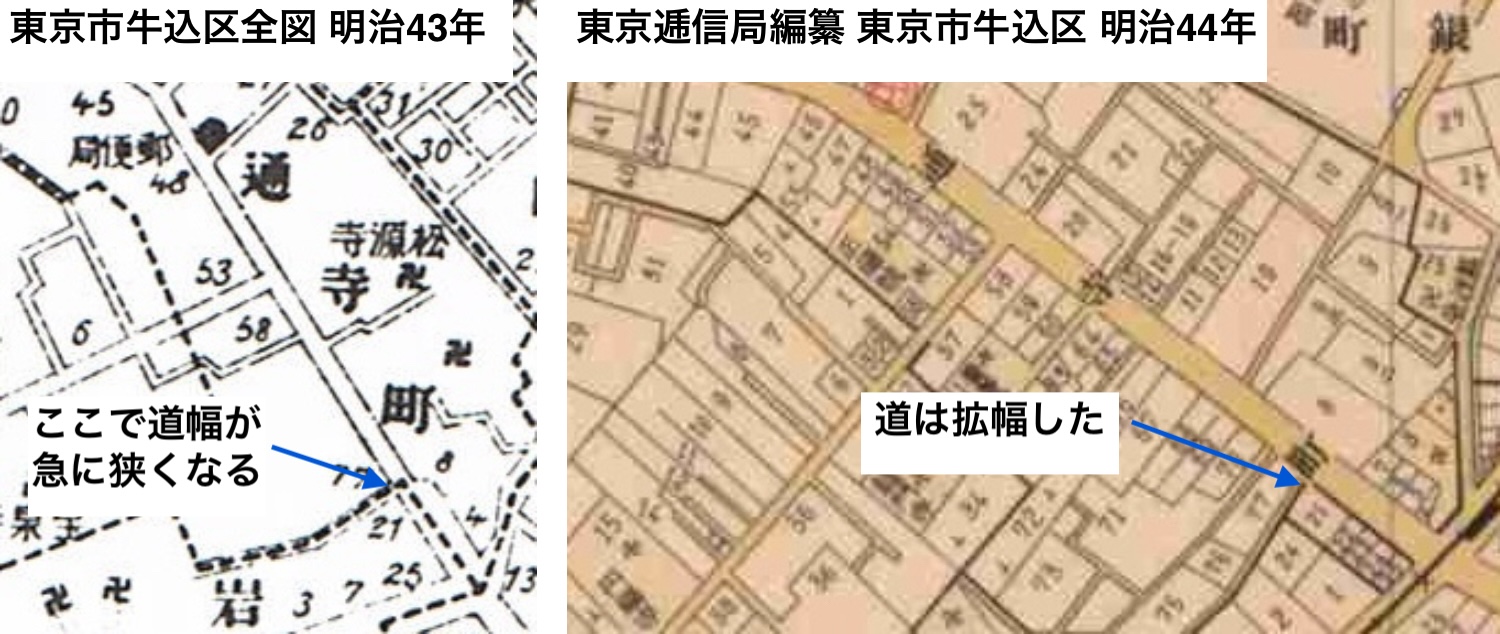

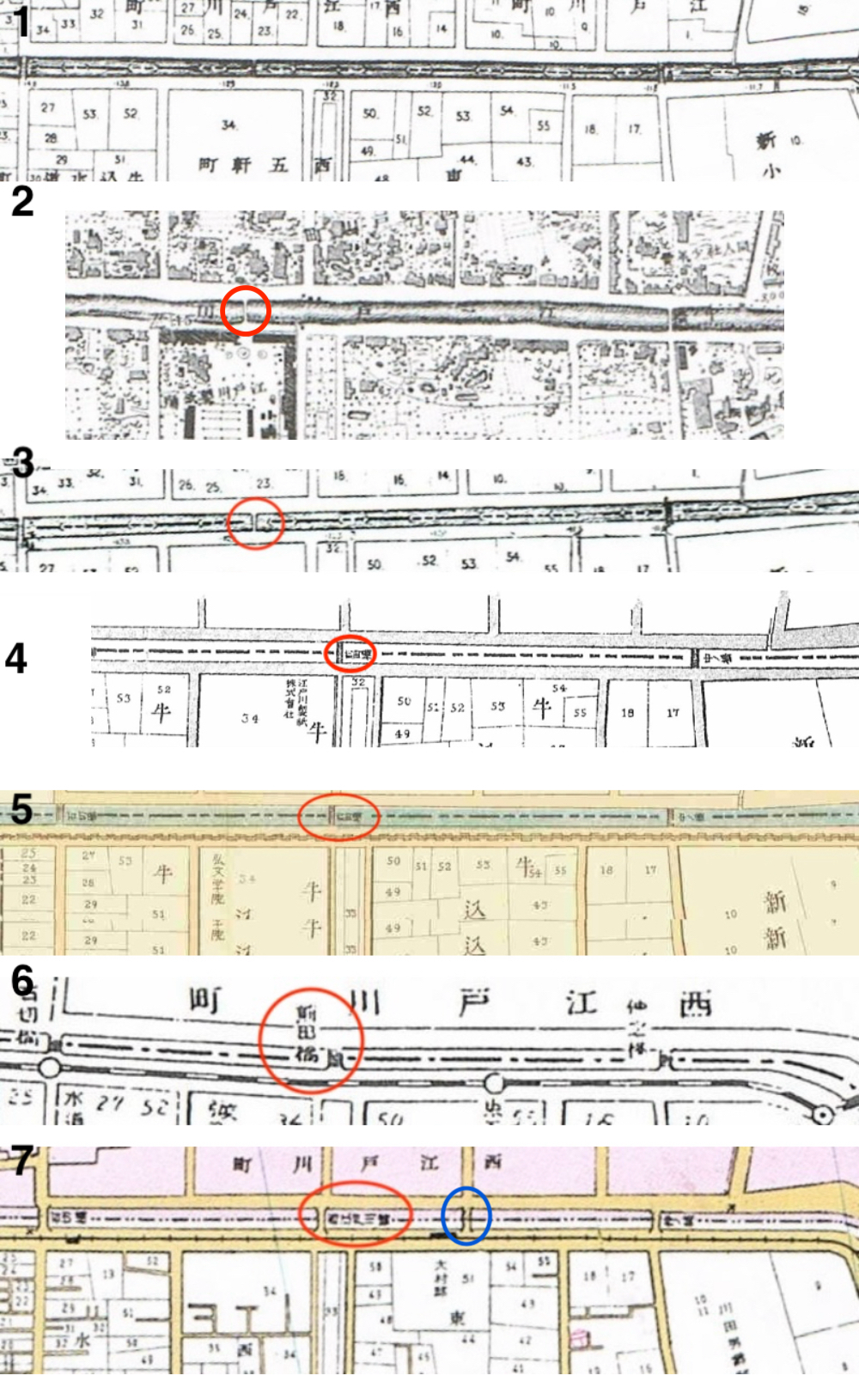

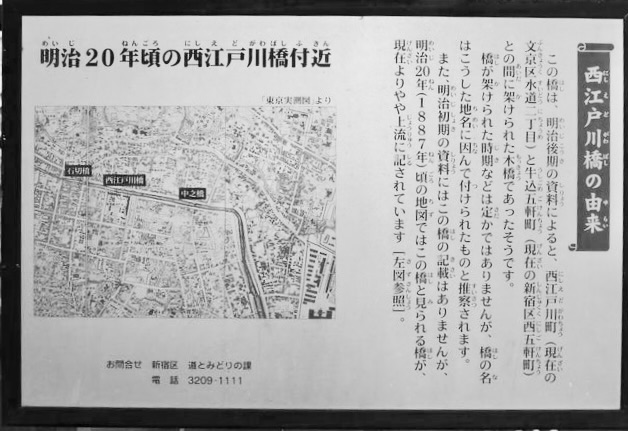

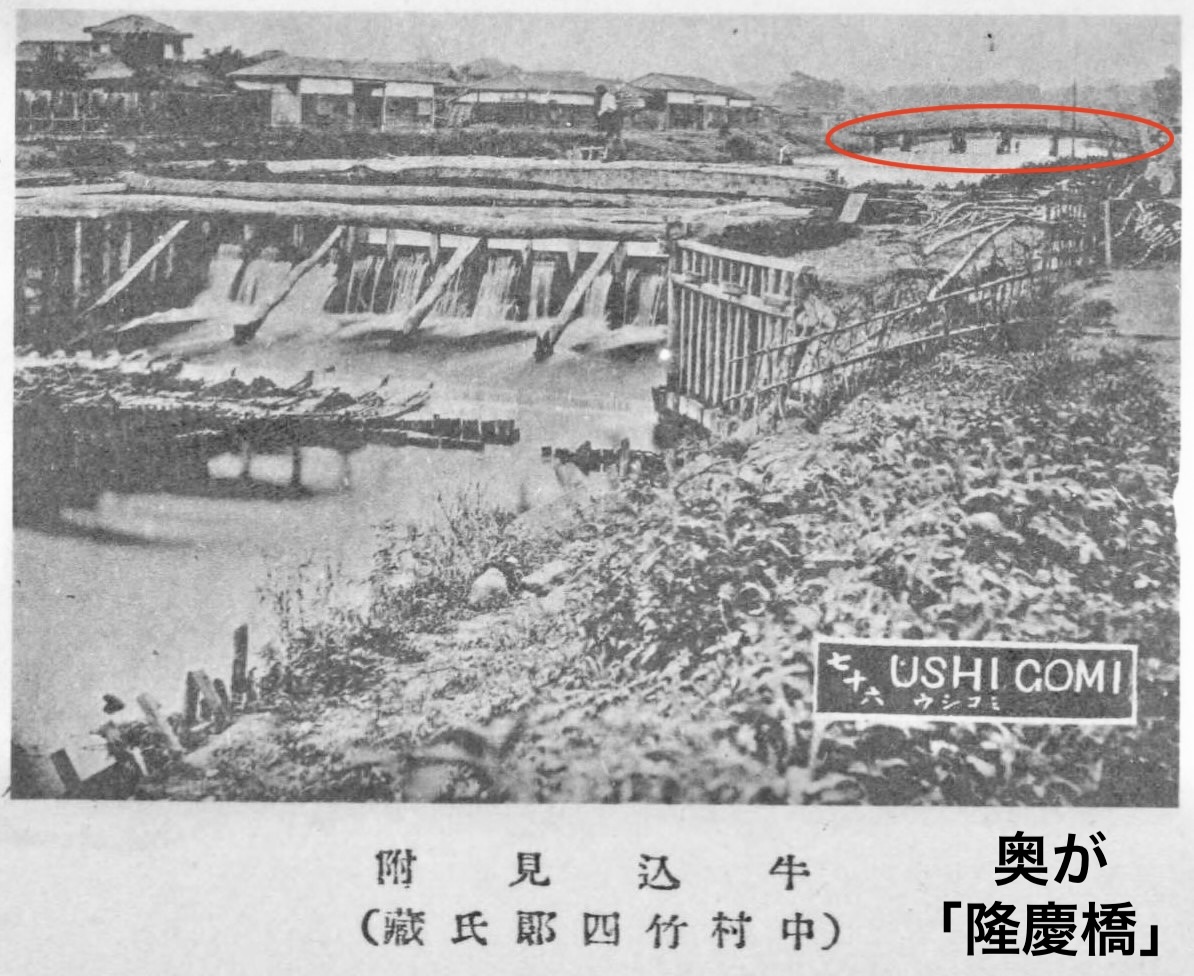

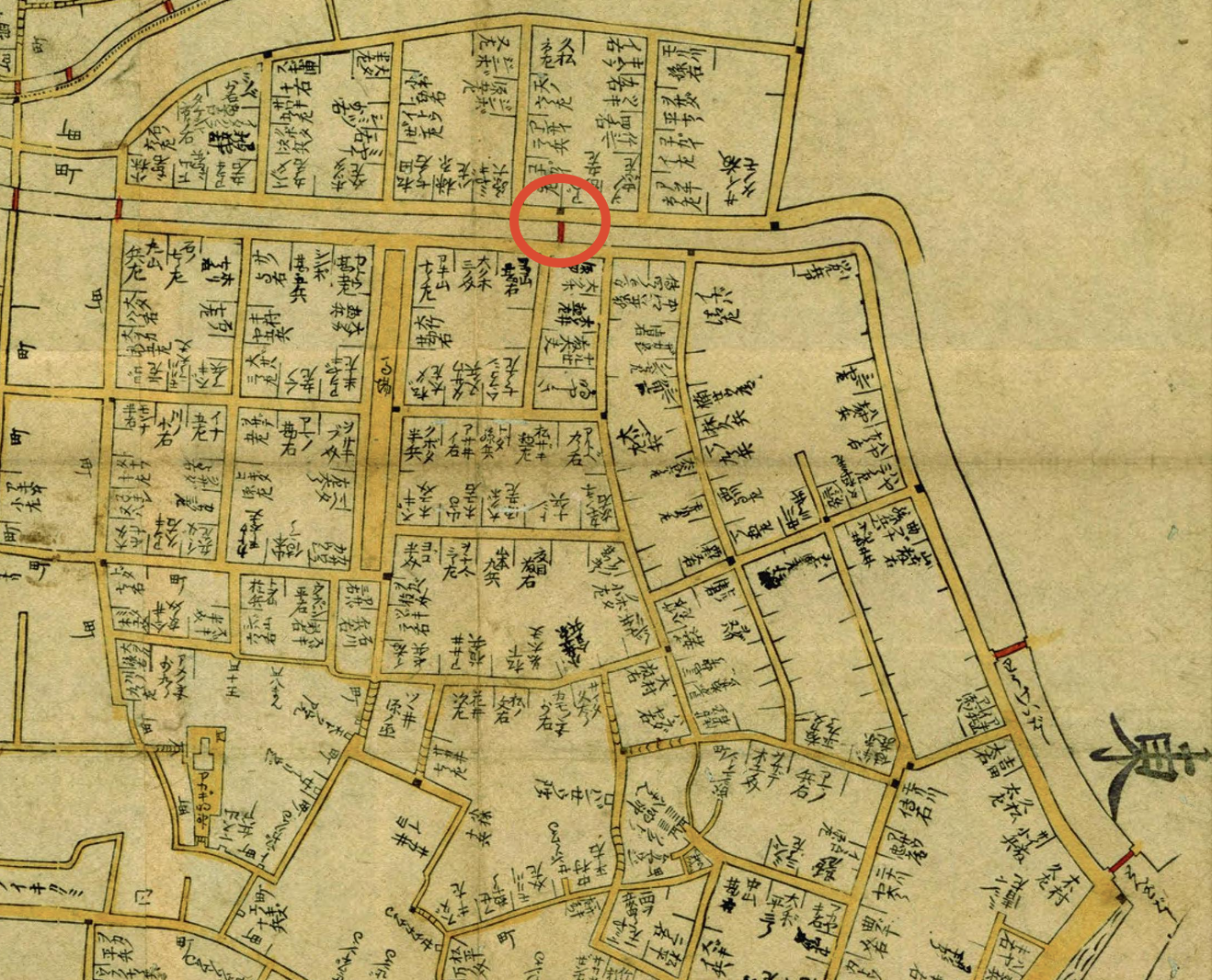

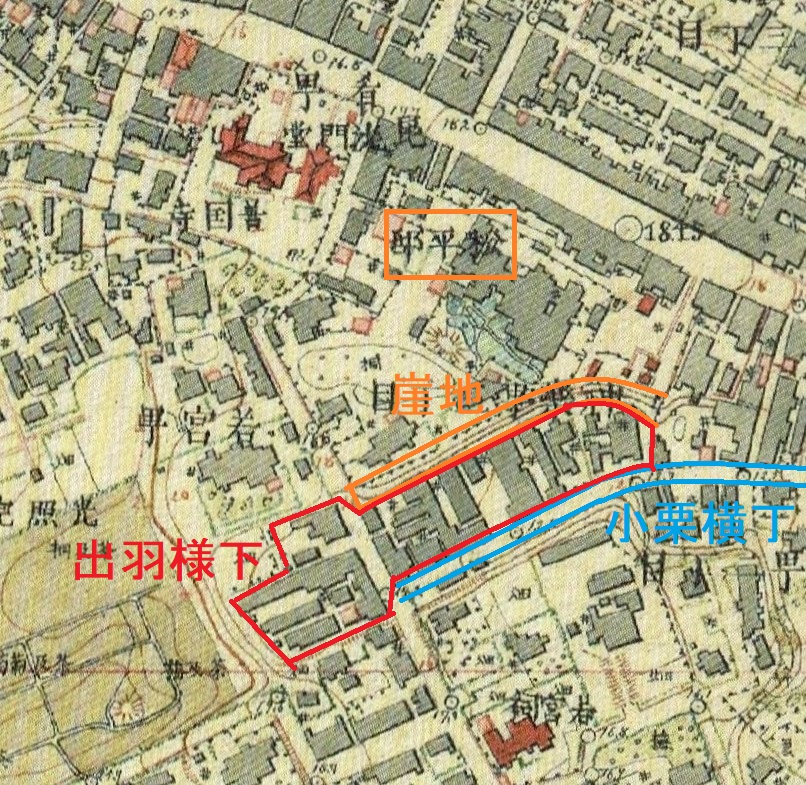

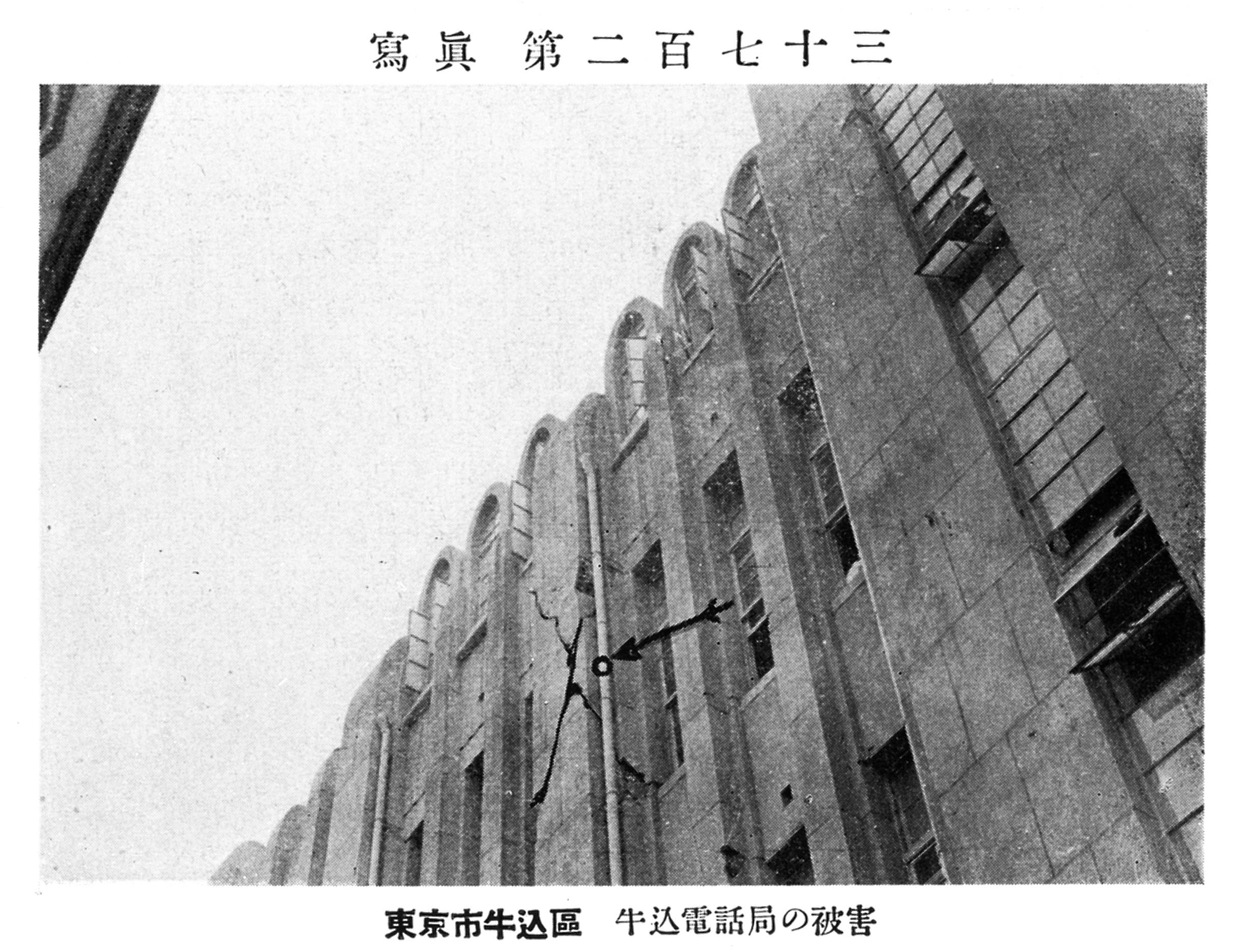

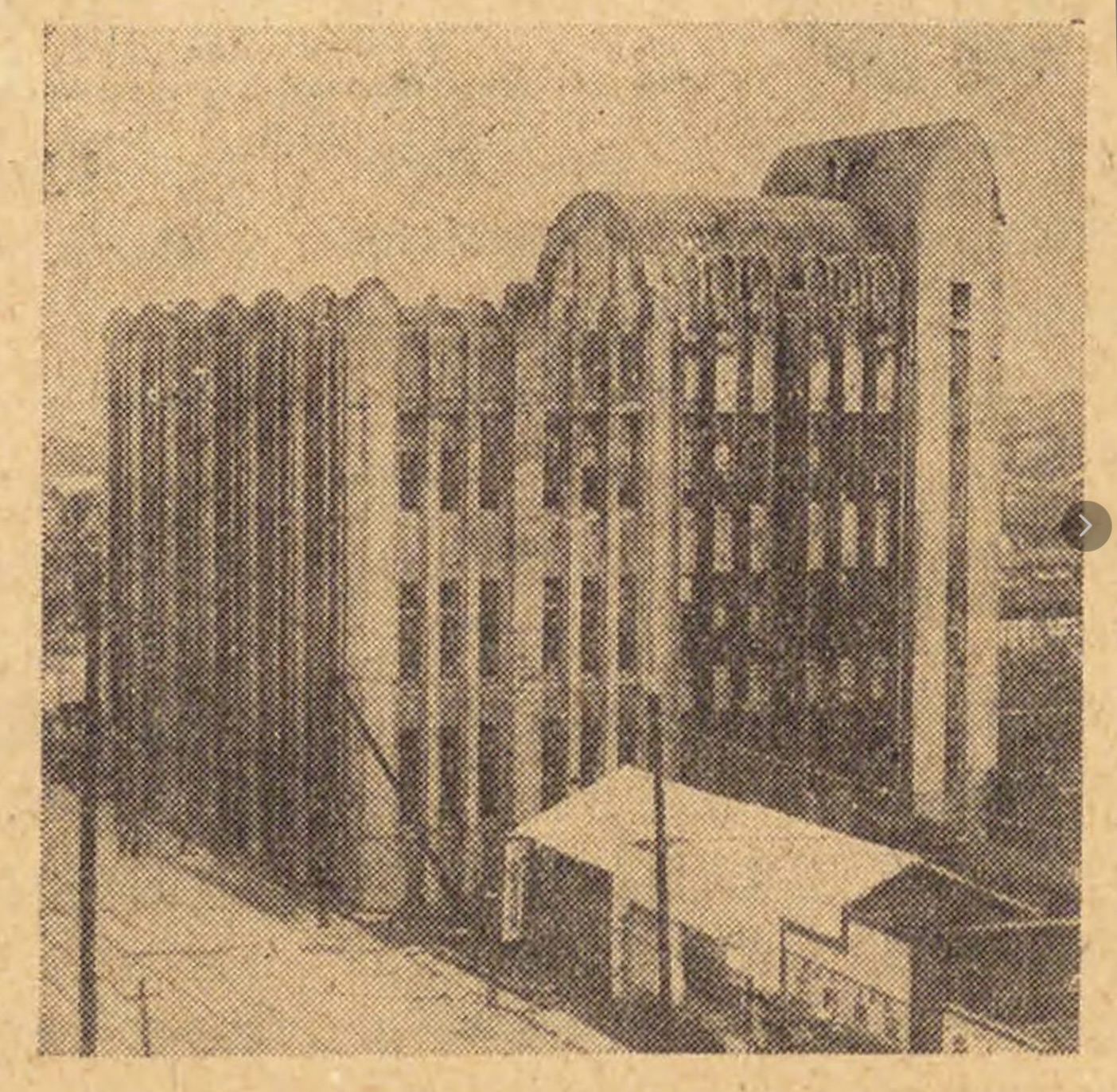

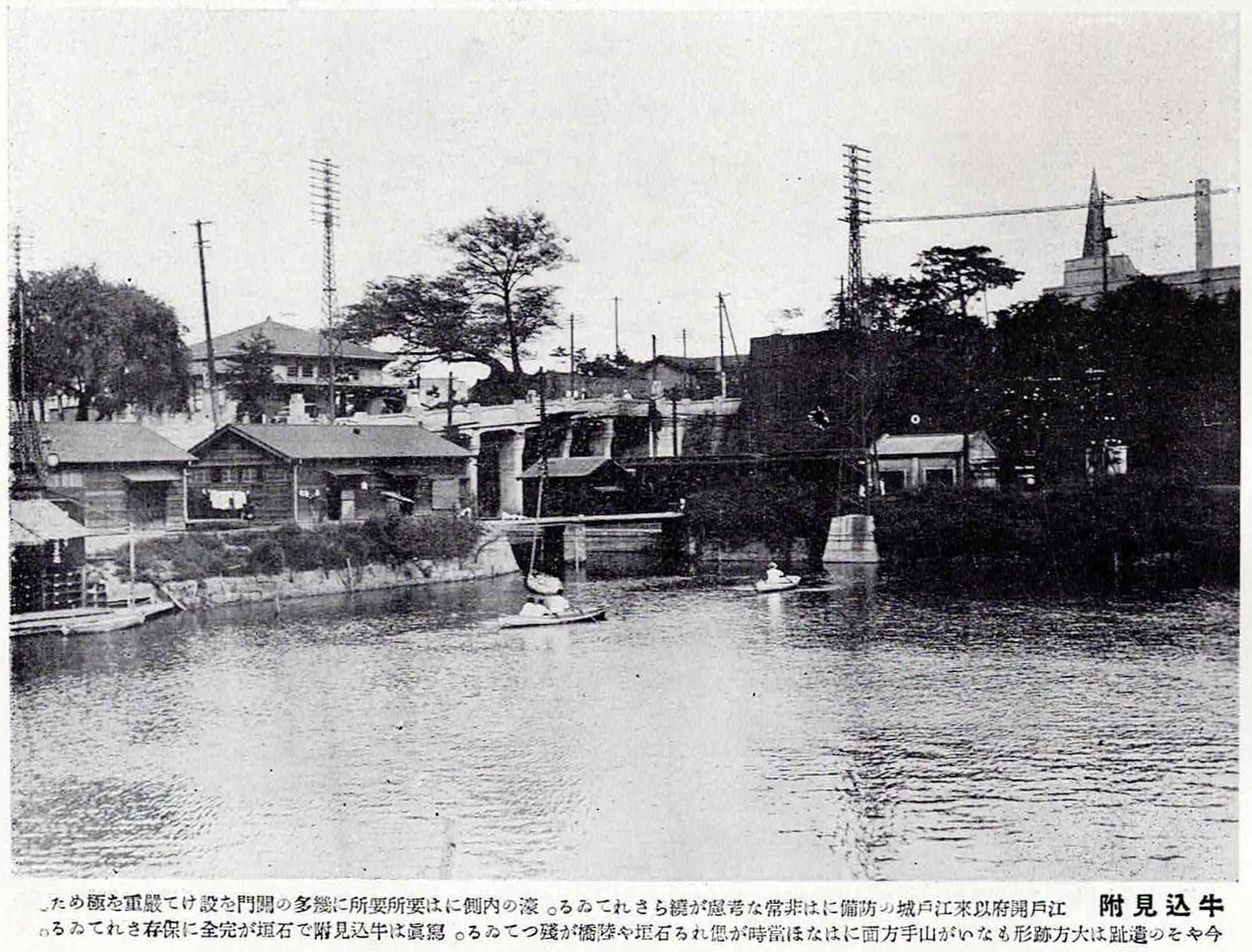

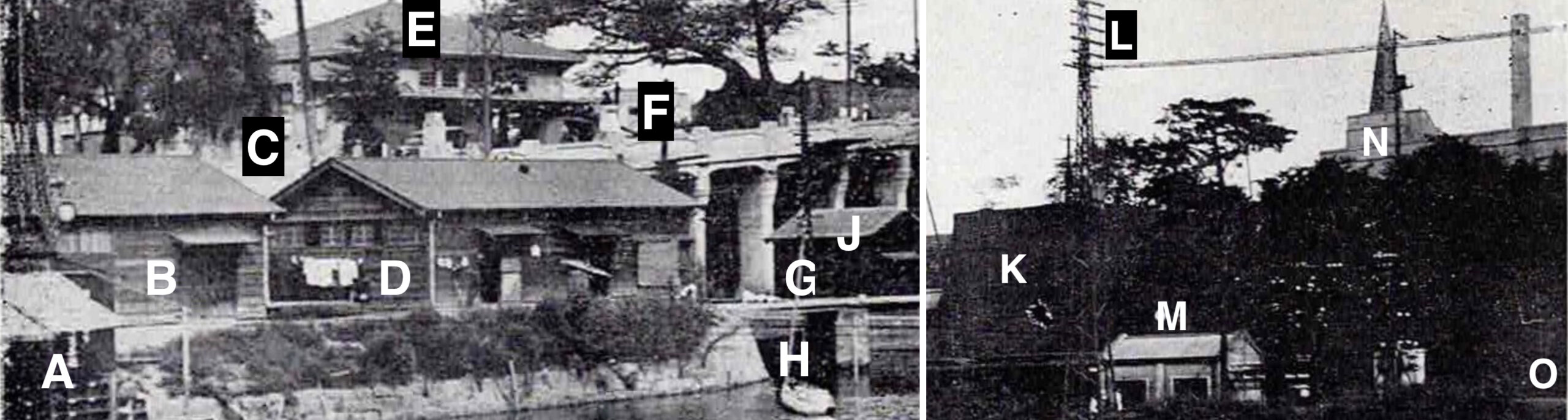

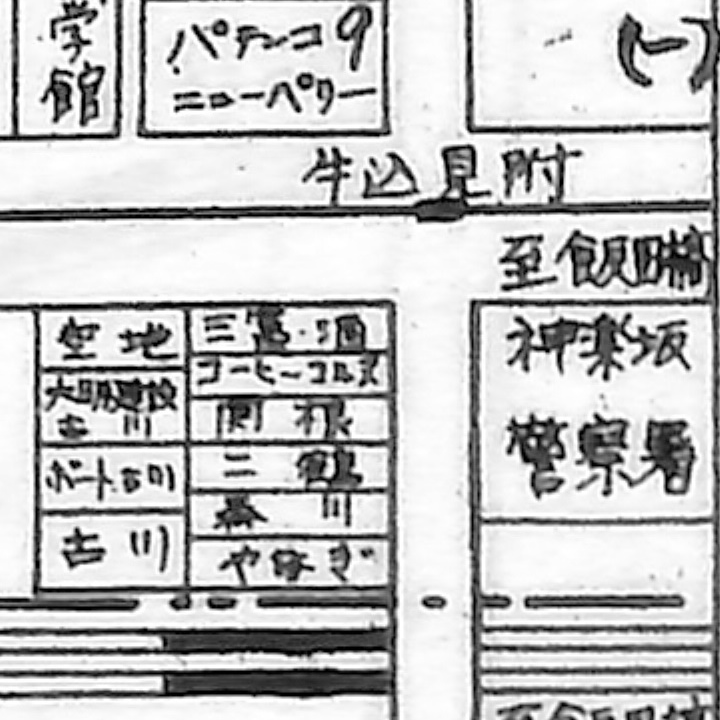

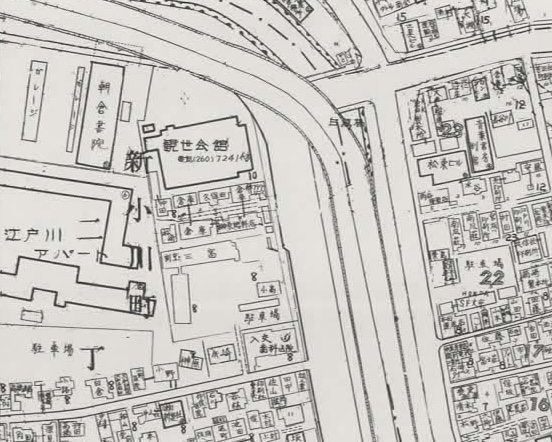

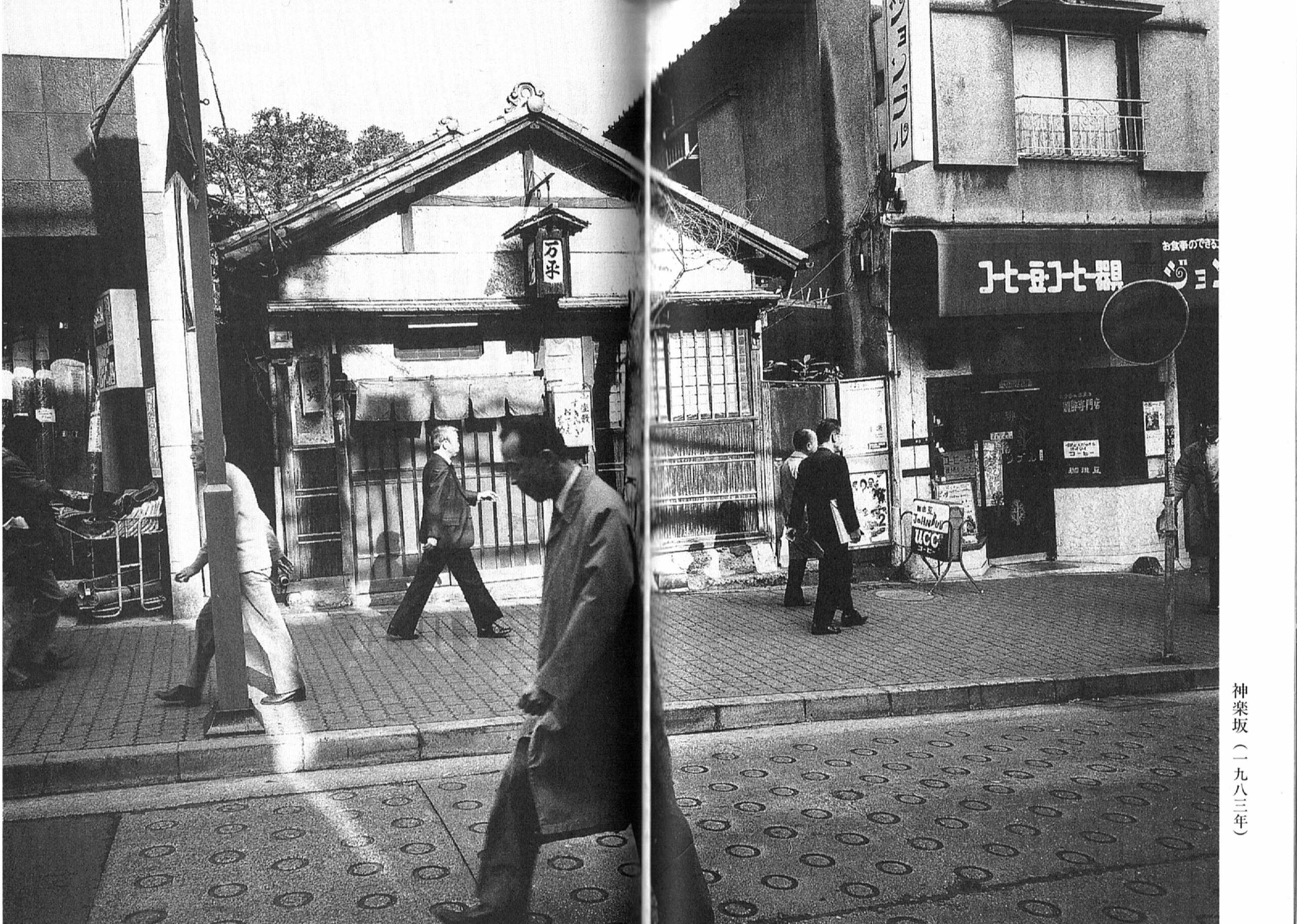

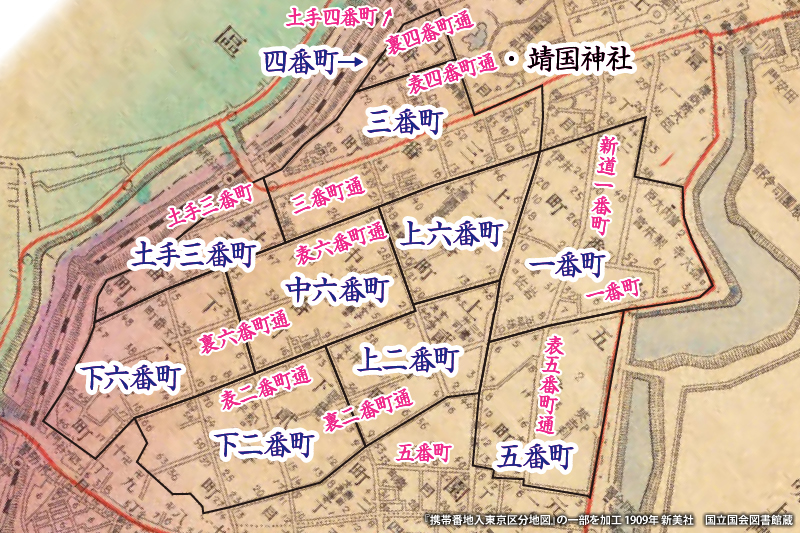

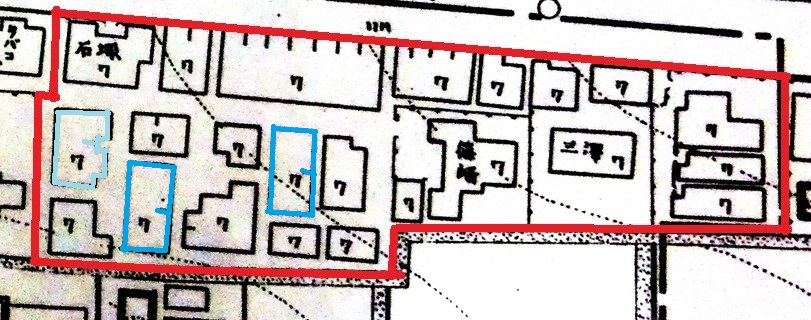

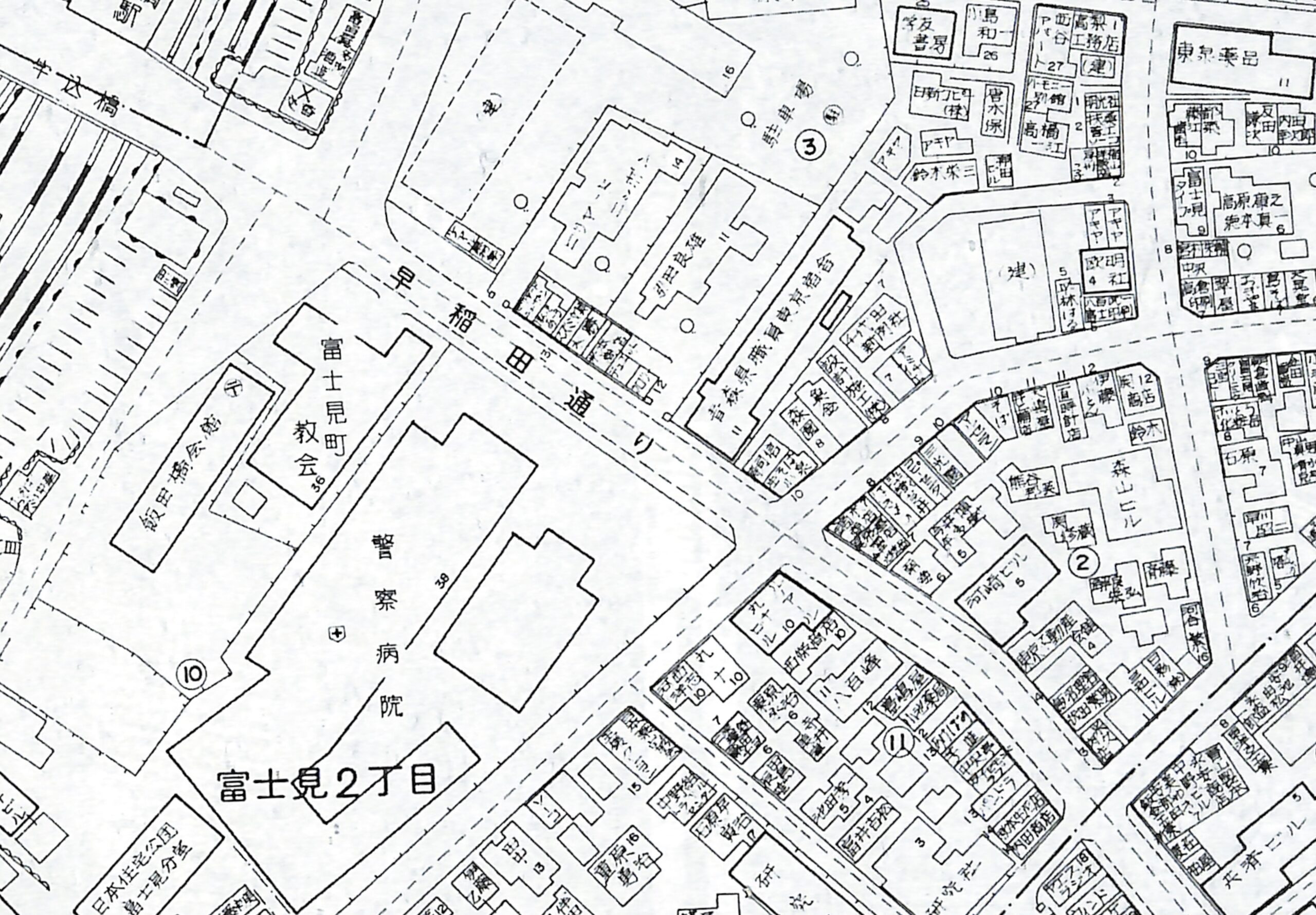

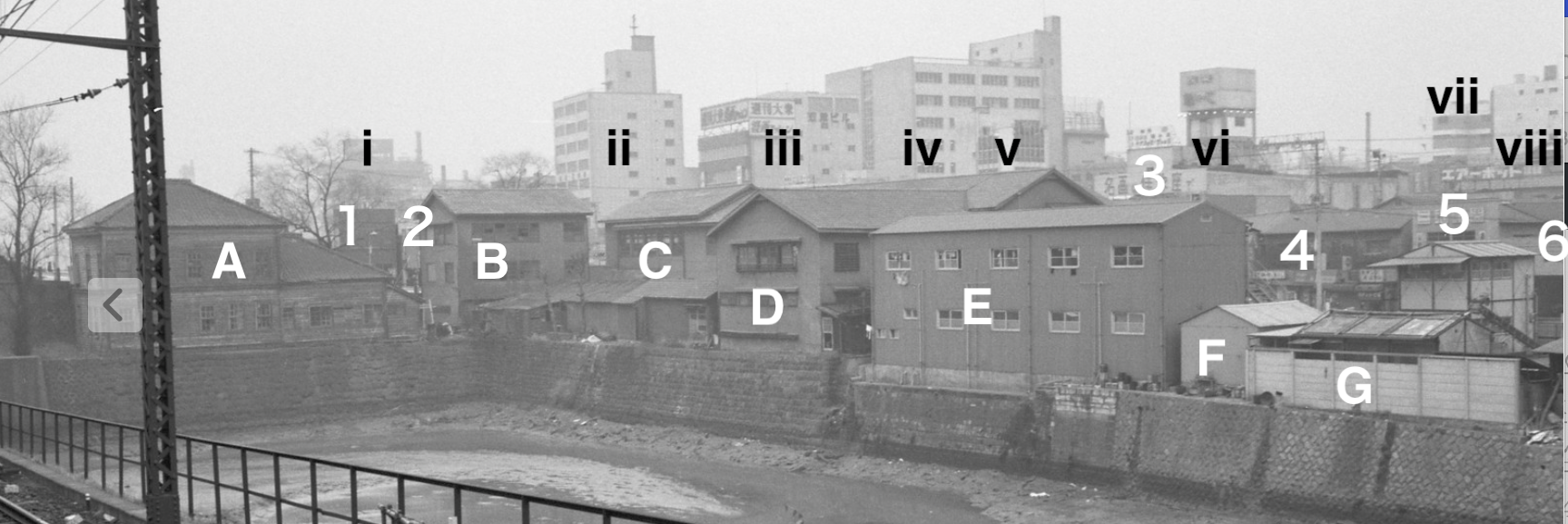

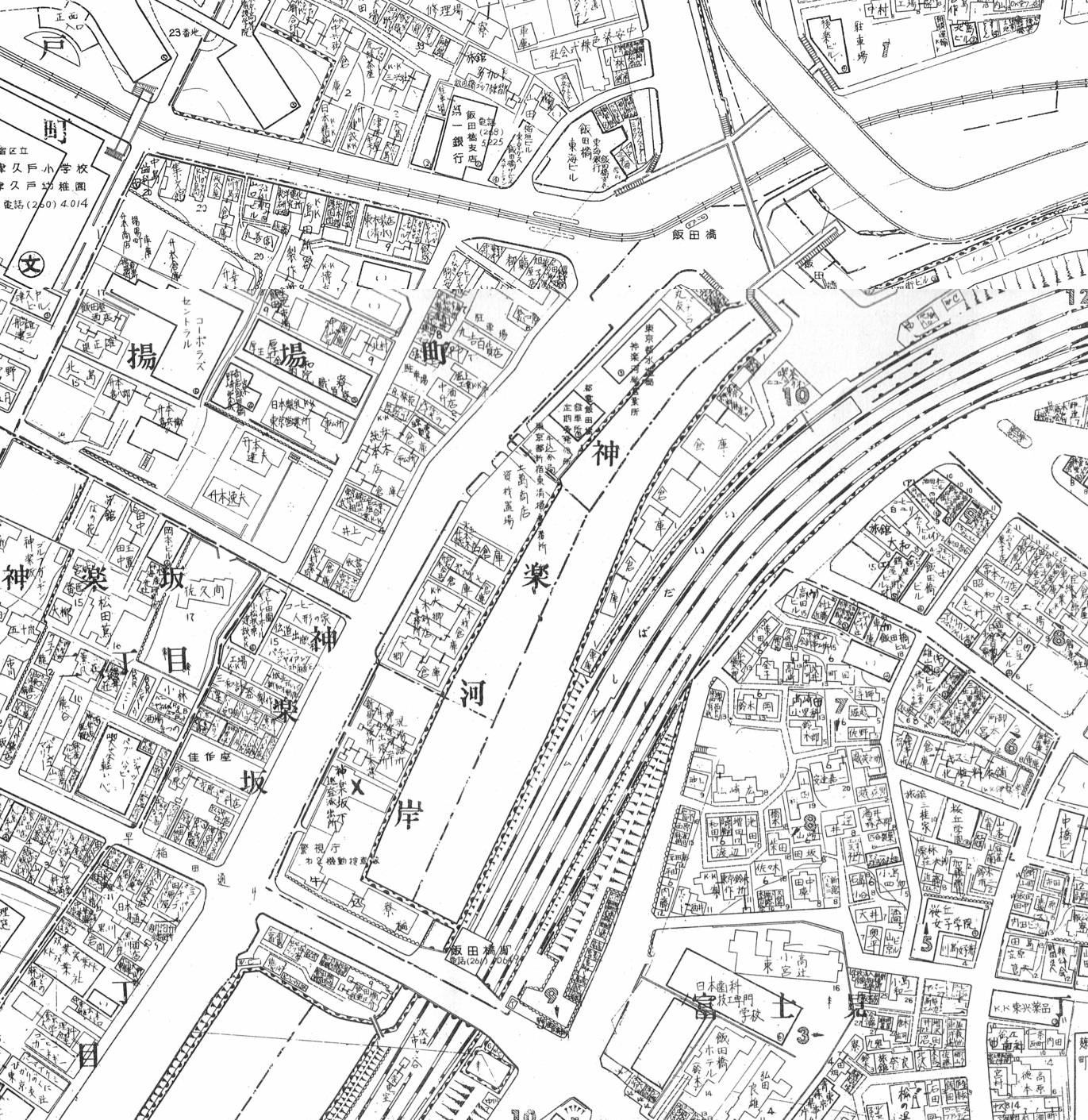

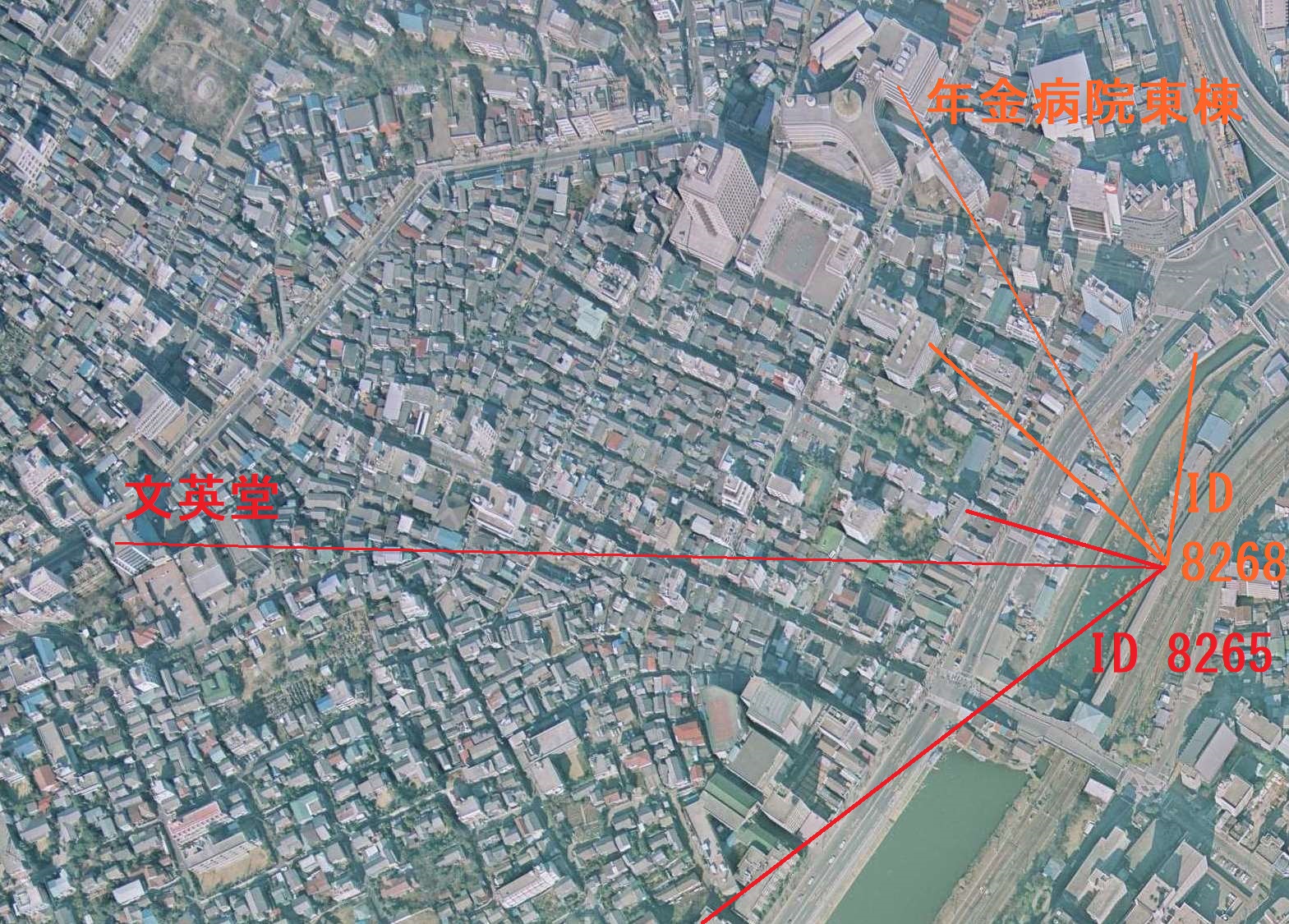

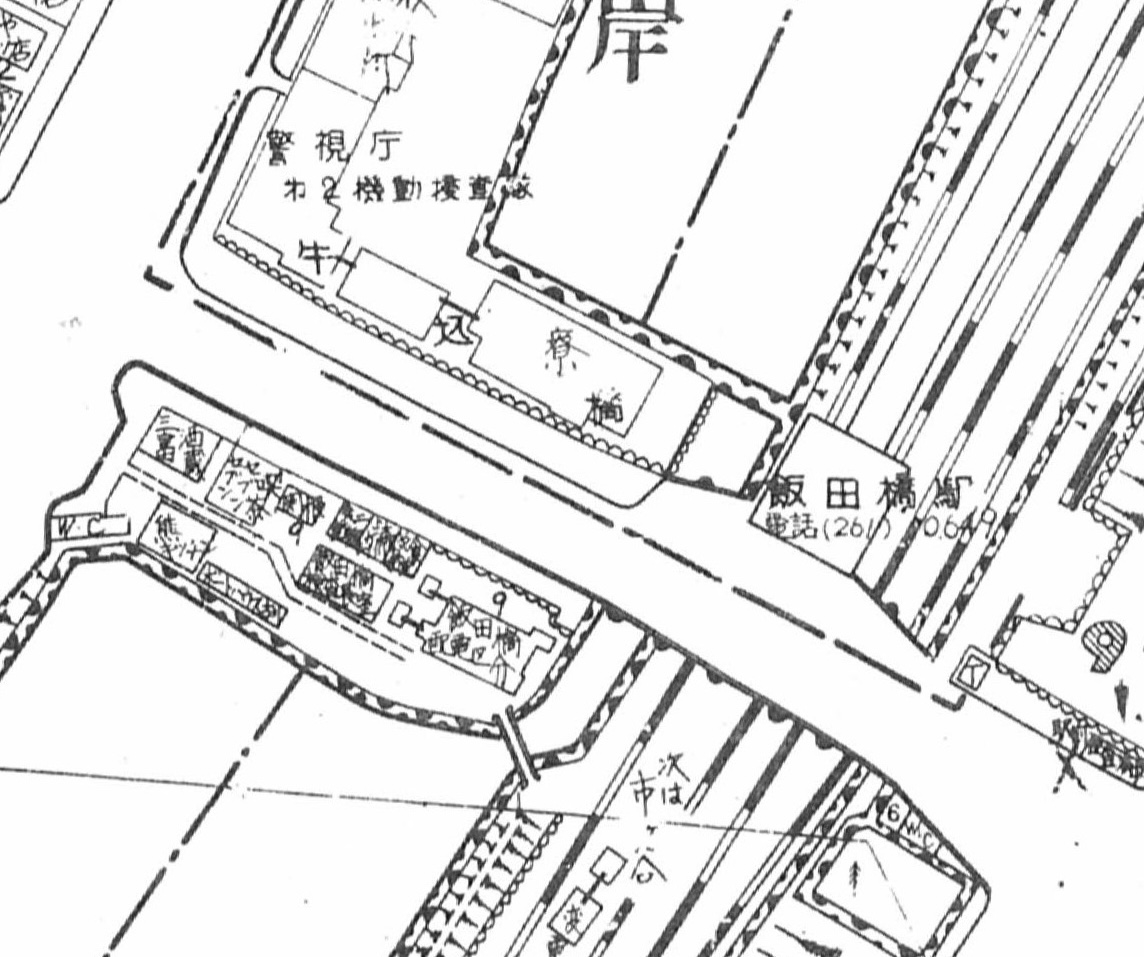

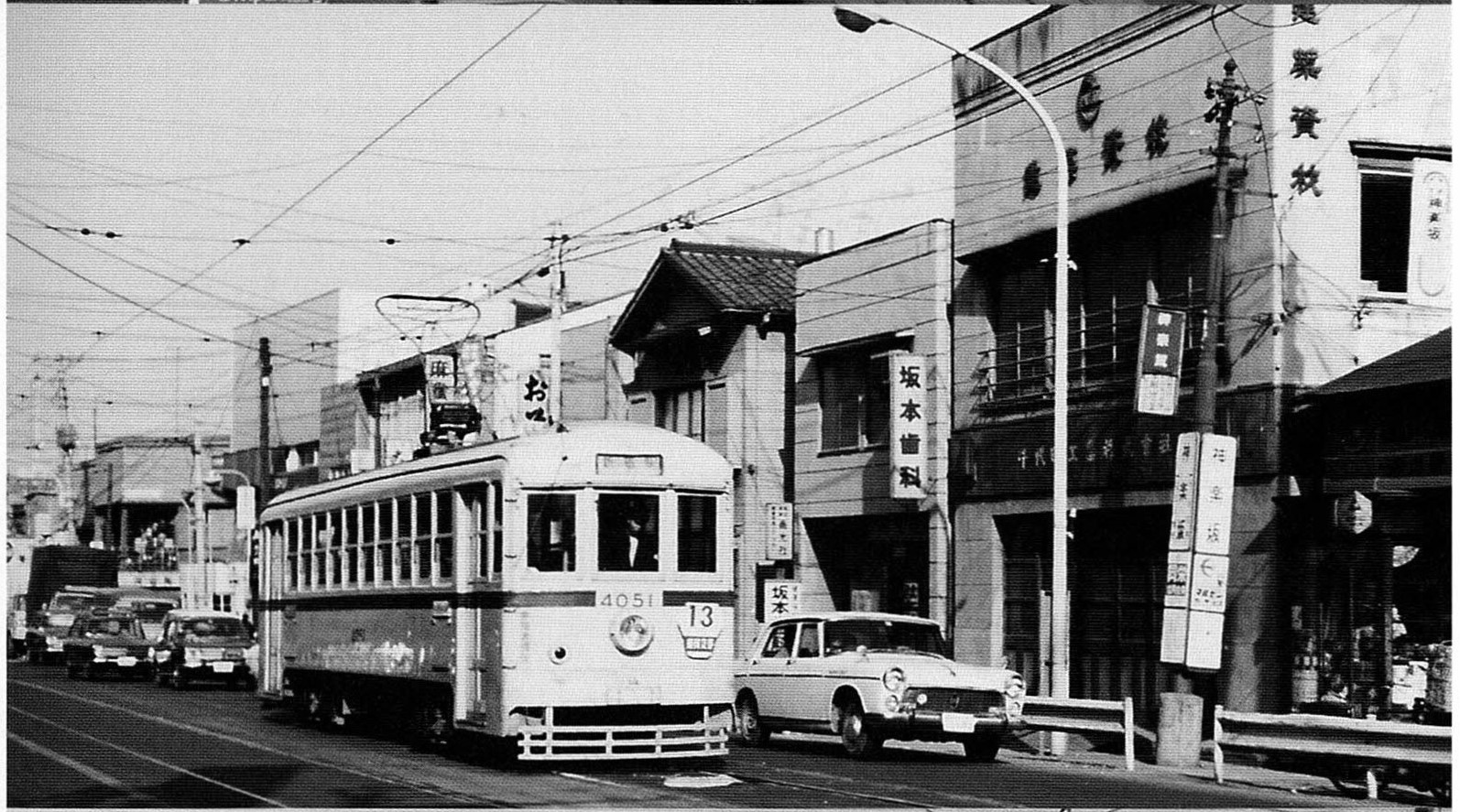

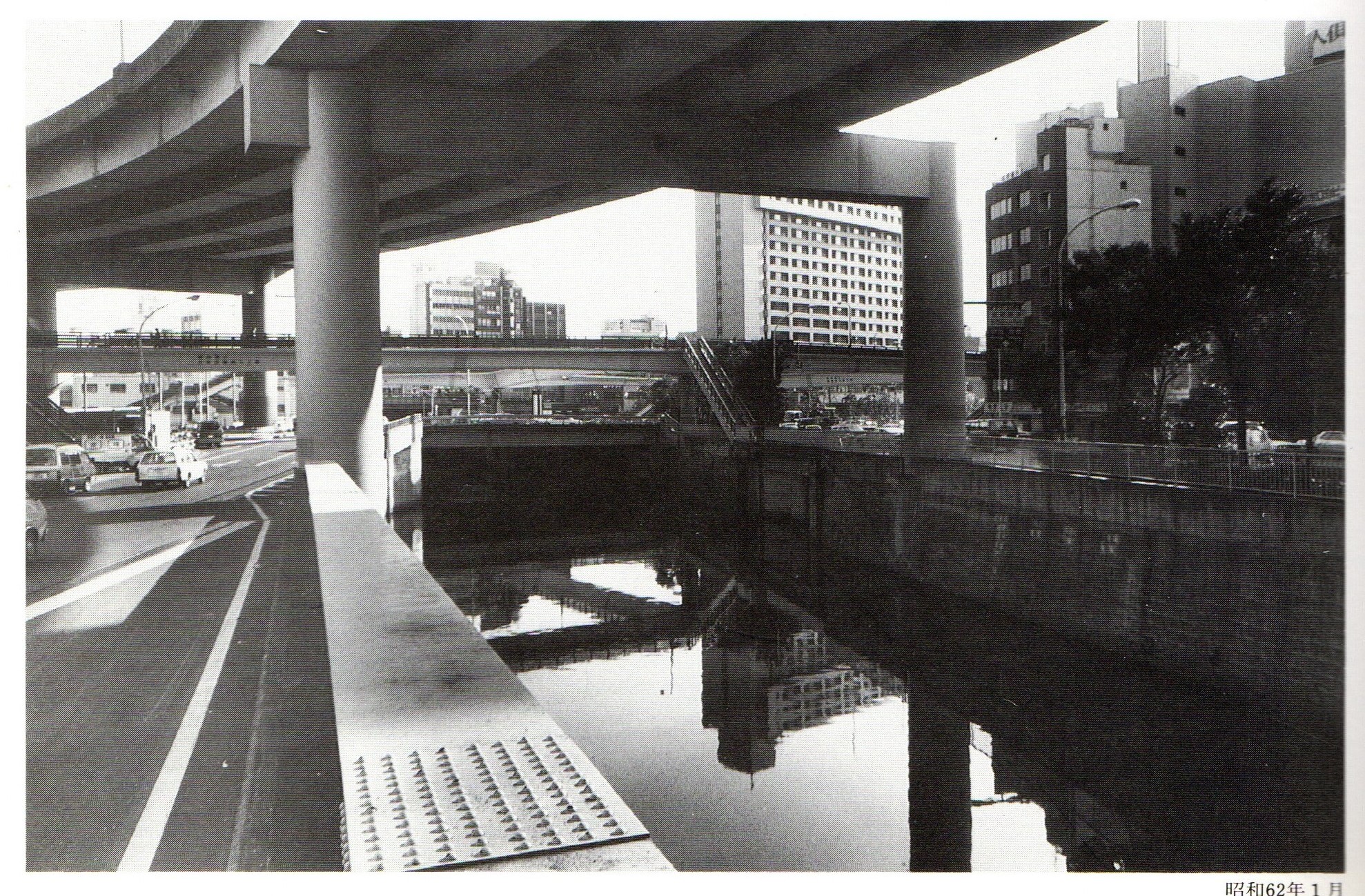

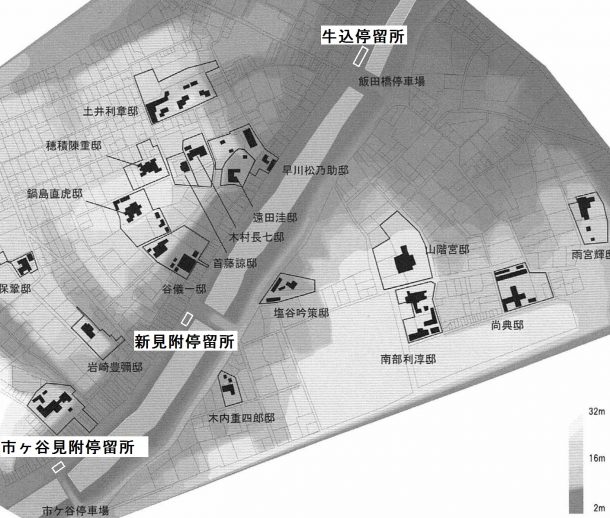

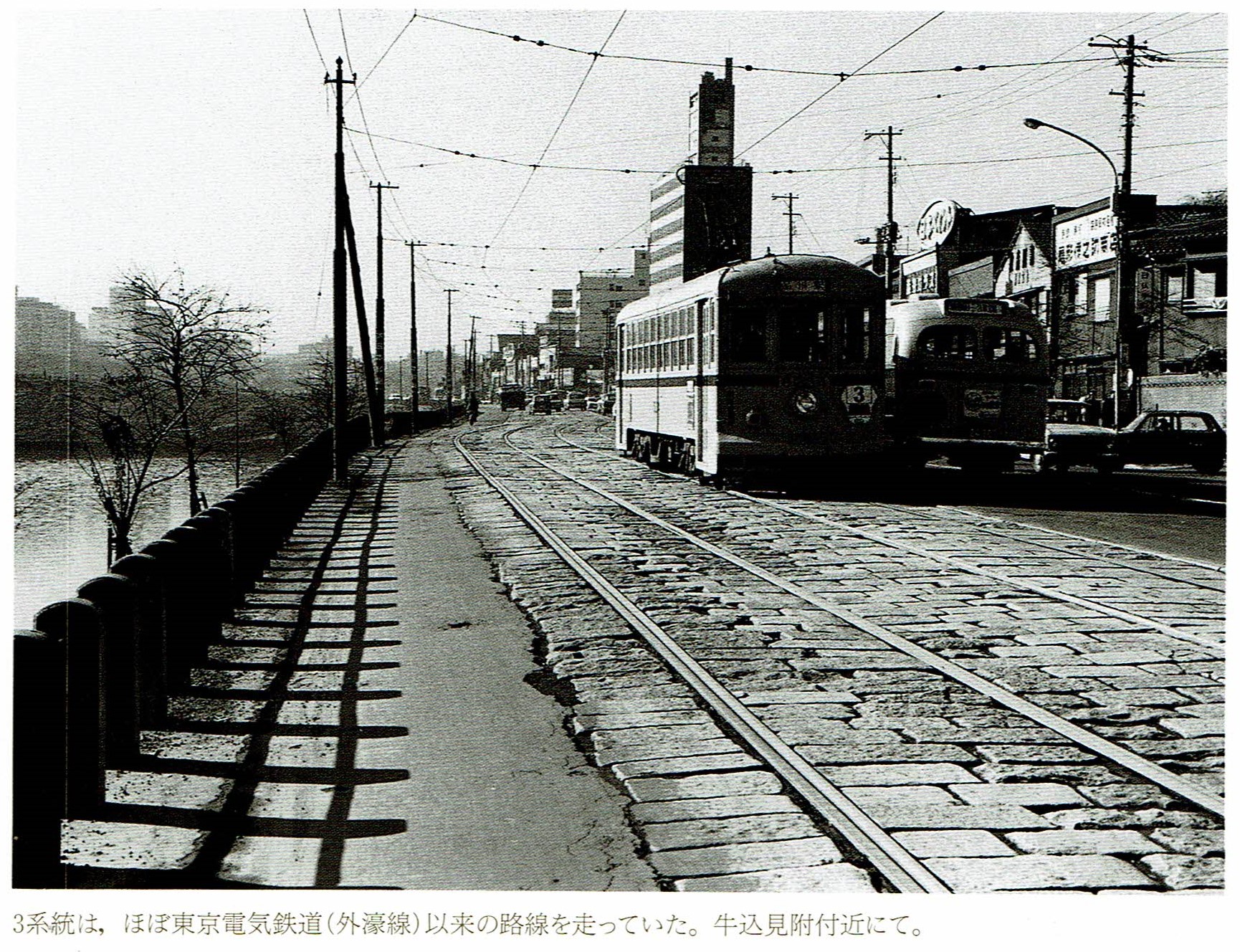

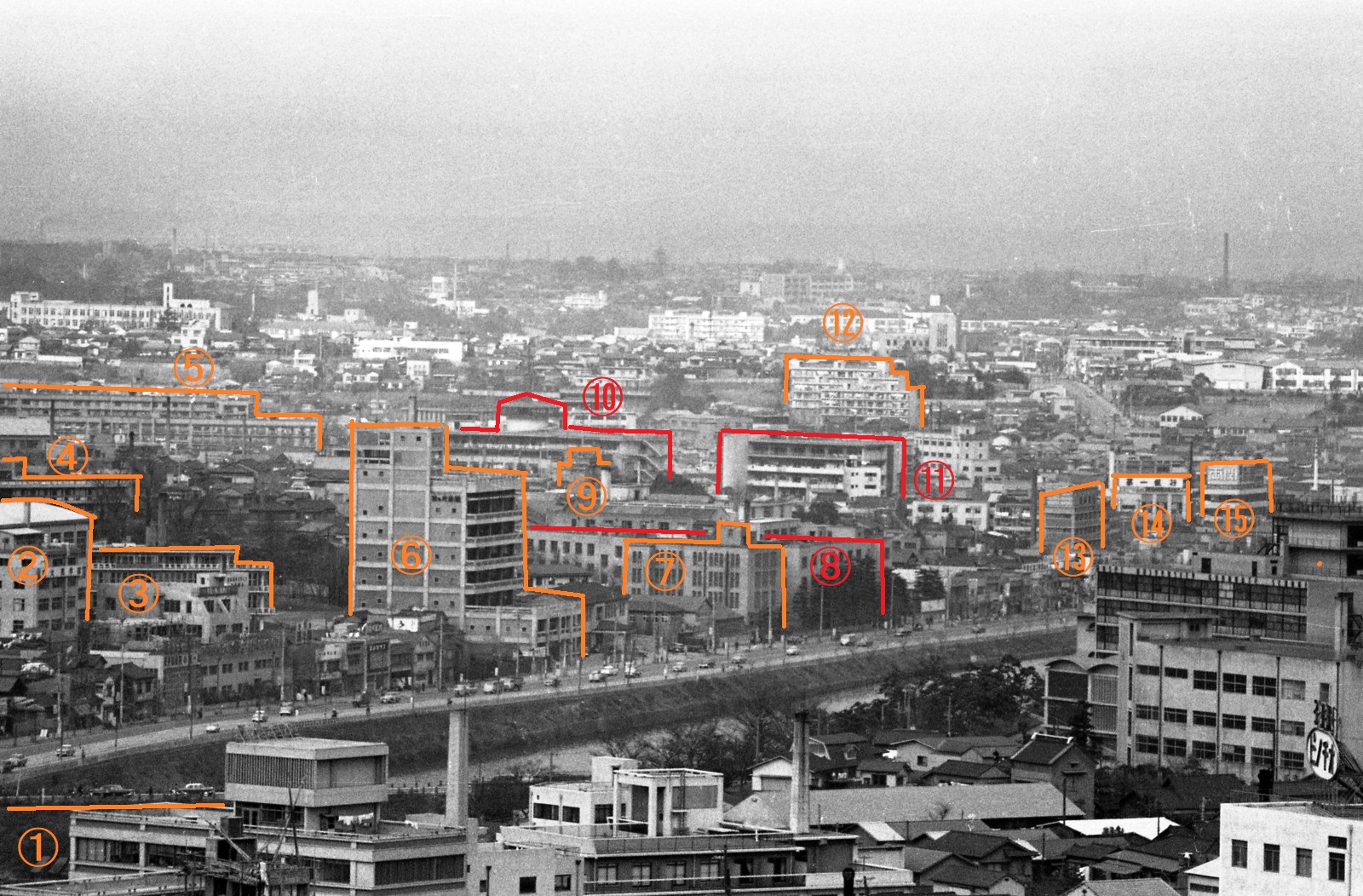

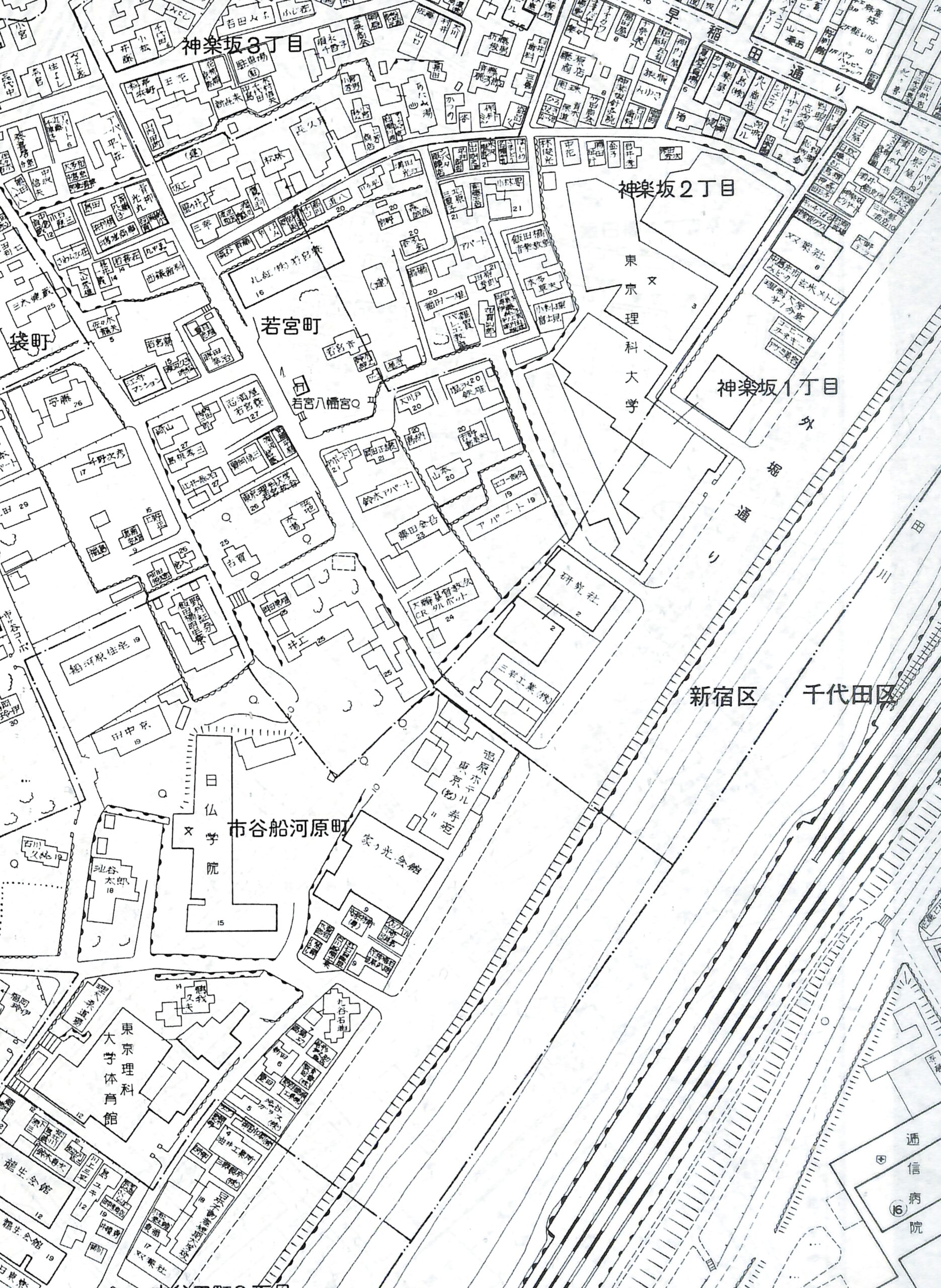

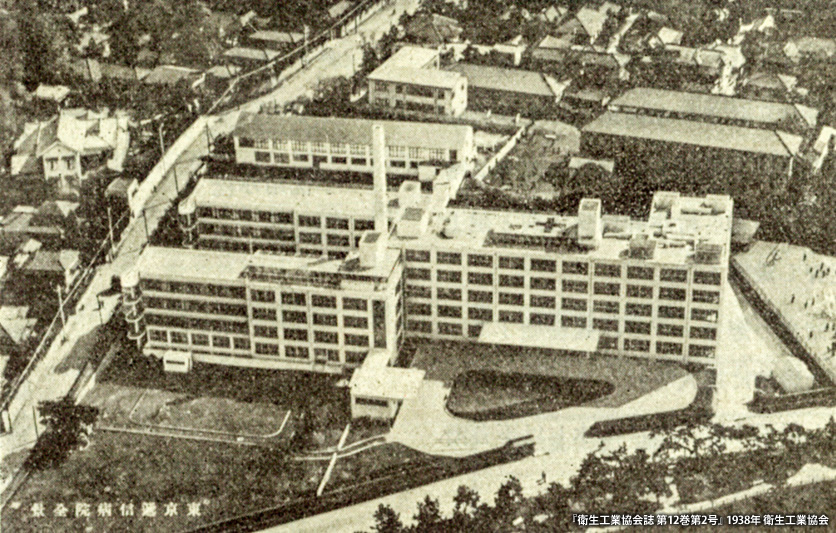

繁華街の核、毘沙門様 毘沙門 様である。正式には善国寺である。文禄4年(1595)に、中央区馬喰町に建立され、寛政4年(1792)に類焼してここに移転してきたものである。本尊の毘沙門天像 遊歴雑記 」中の、江戸七福神詣にはここを入れてあるから、そのころから有名になったのであろう。近代花街年表 」には「明治7年1月24日、牛込肴町 より出火、神楽坂花街全焼す」と出ている。縁日に夜店 を開くようになったのはここが始まりで、明治20年ごろからであった。それ以後は、縁日の夜店といえば神楽坂毘沙門天のことになっていたが、しだいに浅草はじめ方々にも出るようになったのである。山の手七福神 の一つになったのは昭和9年からである。山の手七福神というのは、このほか原町の経王寺(市谷6参照)、東大久保の厳島神社(大久保27参照)、法善寺(大久保25参照)、永福寺(大久保29参照)、西大久保の鬼王神社(大久保2参照)、新宿二丁目の太宗寺(新宿22参照)である。

善国寺の毘沙門天像

毘沙門天像 昭和60年7月5日、有形文化財(彫刻)で登録。遊歴雑記 ゆうれきざっき。著者は江戸小日向廓然寺の住職・津田敬順。文化9年(1812)の隠居から文政12(1829)までの江戸、その近郊、房総から尾張地方に至るまでの名所・旧跡探訪の紀行文。近代花街年表 おそらく『蒐集時代』の一部でしょう。『蒐集時代—近代花街年表・花街風俗展覽會目録・花街賣笑文献目録』2・3号合輯(粋古堂、1936年。再販は金沢文圃閣、2020年)

では、有坂与太郎氏の「郷土玩具大成 第1巻 (東京篇)」(建設社、昭和10年)317頁の「七福神」についてです。最初は谷中七福で、七福神が初めてこの地に設置されたのです。

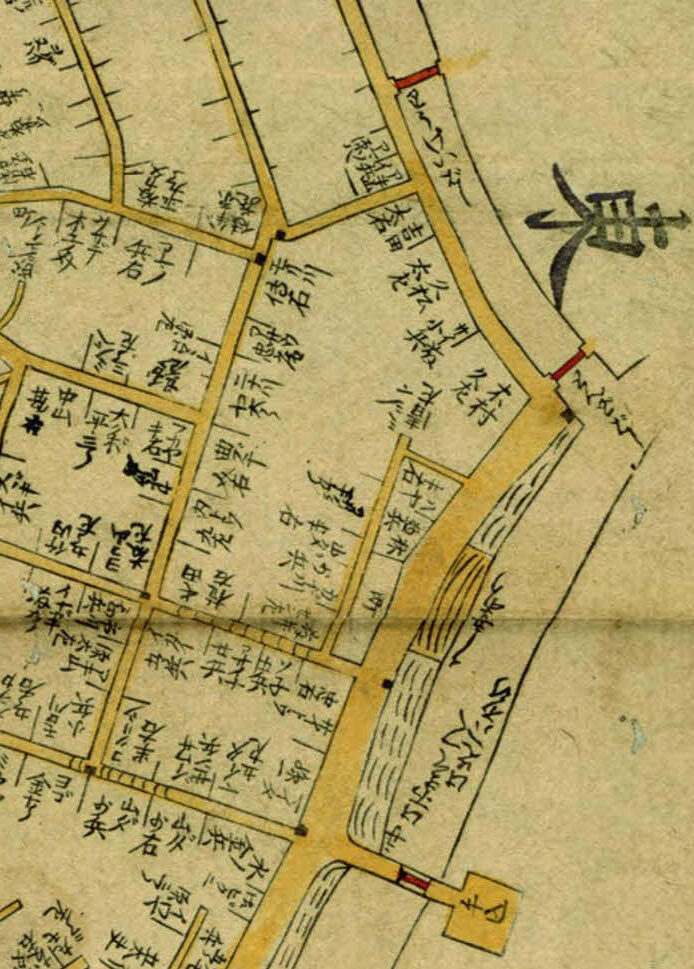

その七福神が江戸に於て初めて設置されたのは元文2年[1737]といわれているが、七福は、俗に谷中 七福と呼ばれ、左の五寺院が挙げられている。即ち

(弁財天)不忍弁天堂(毘沙門)谷中感応寺(寿老人)谷中長安寺(夷えびす 大黒、布袋)日暮里青雲寺(福禄寿)田畑西行庵

つまりこれを順々に巡って福を得ようというので、その中には多分に遊山気分が含まれている。特にこれが流行したのは寛政の初年[1789]あたりからであったとみえて、同じ五年には山東京伝の「花之笑七福参詣」を筆頭とし類似の青本が数冊上梓されている。

谷中 東京都台東区の地名。本郷台と上野台の谷間に位置する。青本 江戸時代に出されていた草双紙の一種。人形浄瑠璃や歌舞伎といった演劇や浮世草子に取材したもの、勧化本や地誌、通俗演義ものや実録もの、一代記ものなどがある。

これは写真の七福神です。高さは13.5糎(cm)しかありません。もう1つ、手に入るのはミニチュアの七福神です。スタンプを押す方がよかったかも。

七福神

また「享和雑記」にも

近頃正月初出に七福神参りといふ事始まりて遊人多く参詣する事となれり

とし、屠蘇機嫌で盛り立てた谷中の七福もどうやら本物になつてきたらしいが、好事魔多しとは神仏の方にもあったらしい。文化の初年[1804]、日暮里布袋堂の住職が強盗のために惨殺されたのが七福の挫折する初まりで、布袋の像は駒込の円通寺へ還され、七福が一福欠けて、さしもの初春絶好の遊山気分にひびが入ったのは是非もない盛衰である。

住職が死亡し、挫折と衰退があり、そこで別の七福神、墨田区の向島七福神が登場します。時代は書いていませんが、おそらく文化元年[1804]以降でしょう。

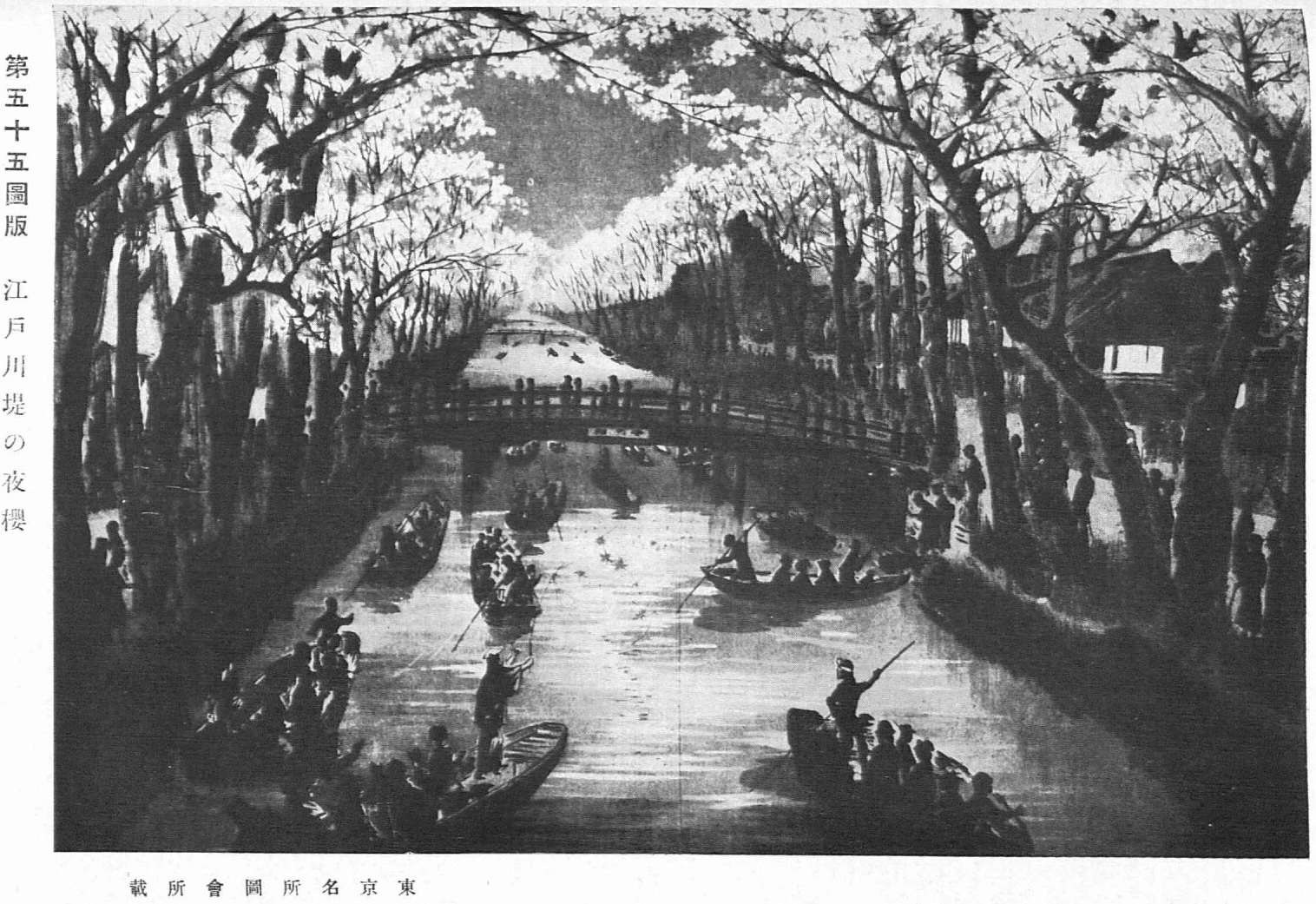

この機に乗じて興った のが向島七福神であって、これは肝入り であり、土地開拓者の一人である梅屋鞠塢 の宣伝よろしきを得たため加速度に売り出してしまった。梅屋敷 を開いた事もまた七福神を創設した事もすべてこの骨董商時代に知遇を得た文人墨客の力に興って大なるものがあった。即ち、鞠塢が七福設置を企画するに当り、先づ喜多武清 の宝船に、角田川 七福遊びと憲斎 が題をした一枚摺 を板行 した。そして、抱ー や蜀山 を抱き込み通人雅客 の清遊 地と云う折紙附の芝居を打ったので、「山師来て何やら裁えし角田川」と白猿 に難じられながらも、半可な酢豆腐 には迎合されるに十分なものがあった。鞠塢自身にして見れば、たただ向島に人がきて呉れればよかったので、どれほど売名的だと云われてもそんな事には亳しも 頑着していなかった。文化元年に梅屋を開いた時も、千蔭 や春海 などの歌人を利用して立派に宣伝効果を挙げていたので、七福の受り込みなどは鞠塢にとって寧ろ朝飯前の仕事であつたかも判らぬ。つまり、向島の七福は谷中のそれと相違し、創設の目的が江戸人の吸引策にあったので、七福神の如きも、寿老人の髯から思いついて対象物のない白髭神社を寿老人に見立てたり、前身の骨董商で既に経験済みの、なにやら得体の知れぬ福禄寿 をさも有難そうに梅屋敷へ持ち込んだりしてみた。春色梅兒誉美 」4編 巻8

由「イエ向島も自由は自由になりましたネ渡り越の舟が、今じゃア六人でかはり/”\に渡しますぜ

藤「くわしく穿つ の、船人の数まではおれも知らなんだ、昨今まで竹屋を呼に声を枯したもんだっけ、それだから故人になった白毛舎が歌に◯ 文々舎側にて当時のよみ 人なりし万守が事なり

須田堤立つゝ呼べど此雪に

藤「この歌も今すこし過ぐると、こんは山谷舟を土手より呼びて、堀へ乗切りし頃の風情を詠めりと、前書が無いとわからなくなりやす」

天保頃の向島は既にこういった著るしい推移が見られた。これは勿論、鞠塢の売名的手段がその発展を急速に促したものであると共に、七福神の存続が向島に対する一般の認識を強めさせる一つの原動力となっていたという事は考えるまでもなかった。

興おこ った おこる。さかんになる。おこす。はじまる。ふるいたつ

肝入り 双方の間を取りもって心を砕き世話を焼くこと。鞠塢氏の百花園が中心となって七福神を立ち上げたのでしょう。

梅屋敷 正式名称は清香庵。伊勢屋喜右衛門の別荘内にあり、300本もの梅の木が植えられ、梅の名所として賑わった。

鞠塢 佐原鞠塢。きくう。江戸後期の文人、本草家。中村座の芝居茶屋に奉公し、骨董店をひらき、財をなし、文化元年、向島寺島村に3000坪の土地を使って花木や草花をあつめ、当初は「新梅屋敷」、後に「向島百花園」で開始。生年は宝暦12年。没年は天保2年8月29日。70歳。「向島百花園」は、昭和13年、全てを東京市に寄付し、現在、都立庭園の1つ。

喜多武清 きた ぶせい。1776-1857。江戸後期の画家

角田川 すみだがわ。隅田川の別表記

憲斎 中川憲斎。なかがわ けんさい。江戸後期の書家。

一枚摺 いちまいずり。紙一枚に印刷すること

板行 はんこう。書籍・文書などを版木で印刷して発行すること

抱ー 酒井抱一。さかい ほういつ。江戸後期の絵師、俳人。

蜀山 蜀山人。しょくさんじん。大田南畝。江戸後期の文人・狂歌師

通人雅客 つうじん。あることに精通している人。がかく。風雅を理解し愛好する人。

清遊 せいゆう。世俗を離れて風流な遊びをすること

白猿 五代目市川団十郎白猿。芭蕉の「山路来て なにやらゆかし すみれ草」をもじって「山師来て 何やら裁えし 角田川」と詠んだ

半可な酢豆腐 知ったかぶりの若旦那が、腐って酸っぱくなった豆腐を食べさせられ、酢豆腐だと答える落語から。知ったかぶり。半可通。

亳しも こうも。「毫」は細い毛の意。少しも。ちっとも。おそらく「亳しも」と書いて「少しも」と読むのでしょう。

千蔭 加藤

千ち 蔭かげ 。江戸中期から後期にかけての国学者・歌人・書家。

春海 村田春海。むらたはるみ。江戸中期・後期の国学者・歌人。

福禄寿 ふくろくじゅ。七福神の一神。幸福・

俸禄ほうろく ・長寿命をさずける神

春色しゅんしょく 梅うめ 兒誉美ごよみ しゅんしょくうめごよみ。人情本。江戸深川の花柳界を背景に描いた、写実的風俗小説。

穿つ 穴をあける。押し分けて進む。人情の機微に巧みに触れる。物事の本質をうまく的確に言い表す。新奇で凝ったことをする。

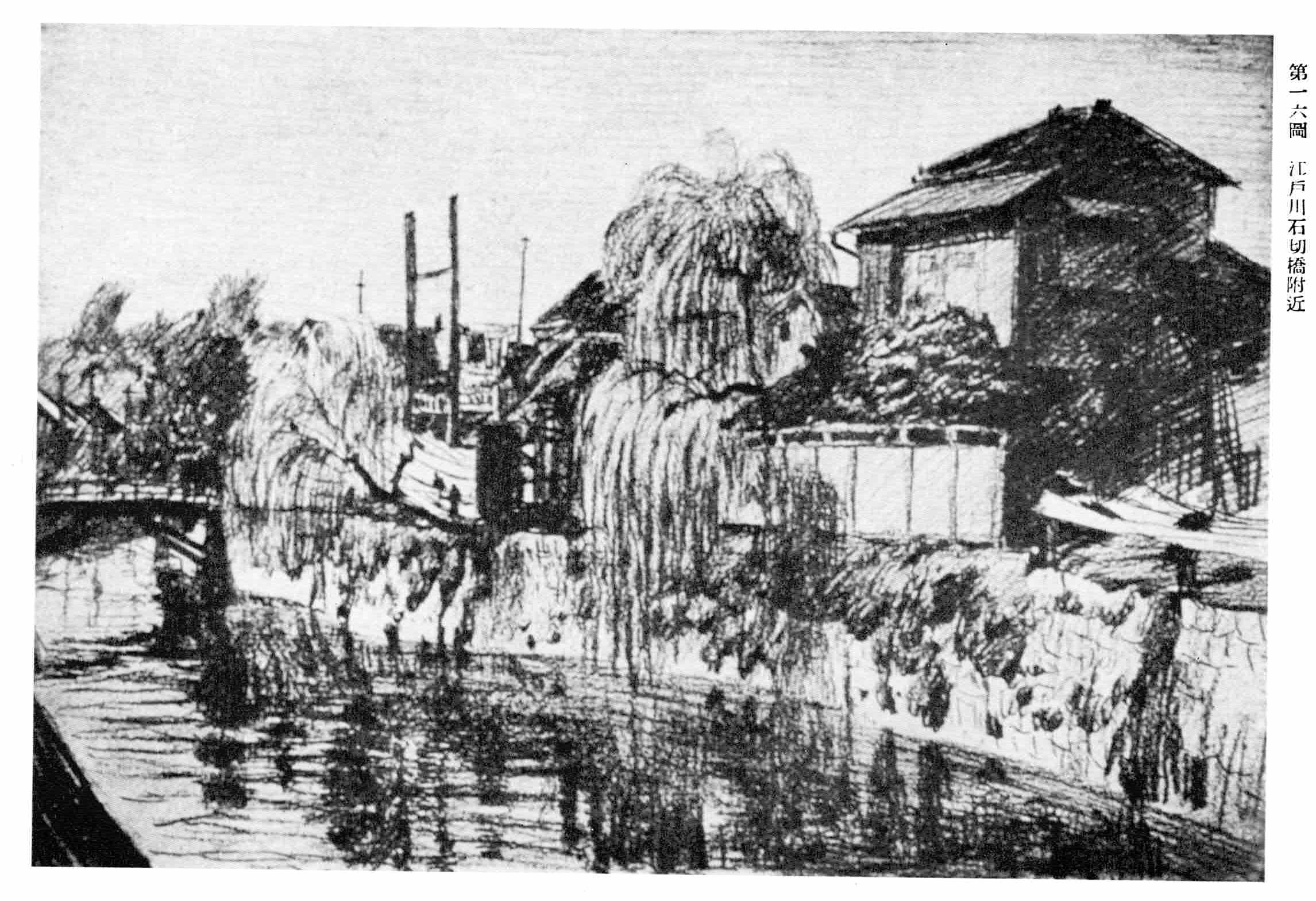

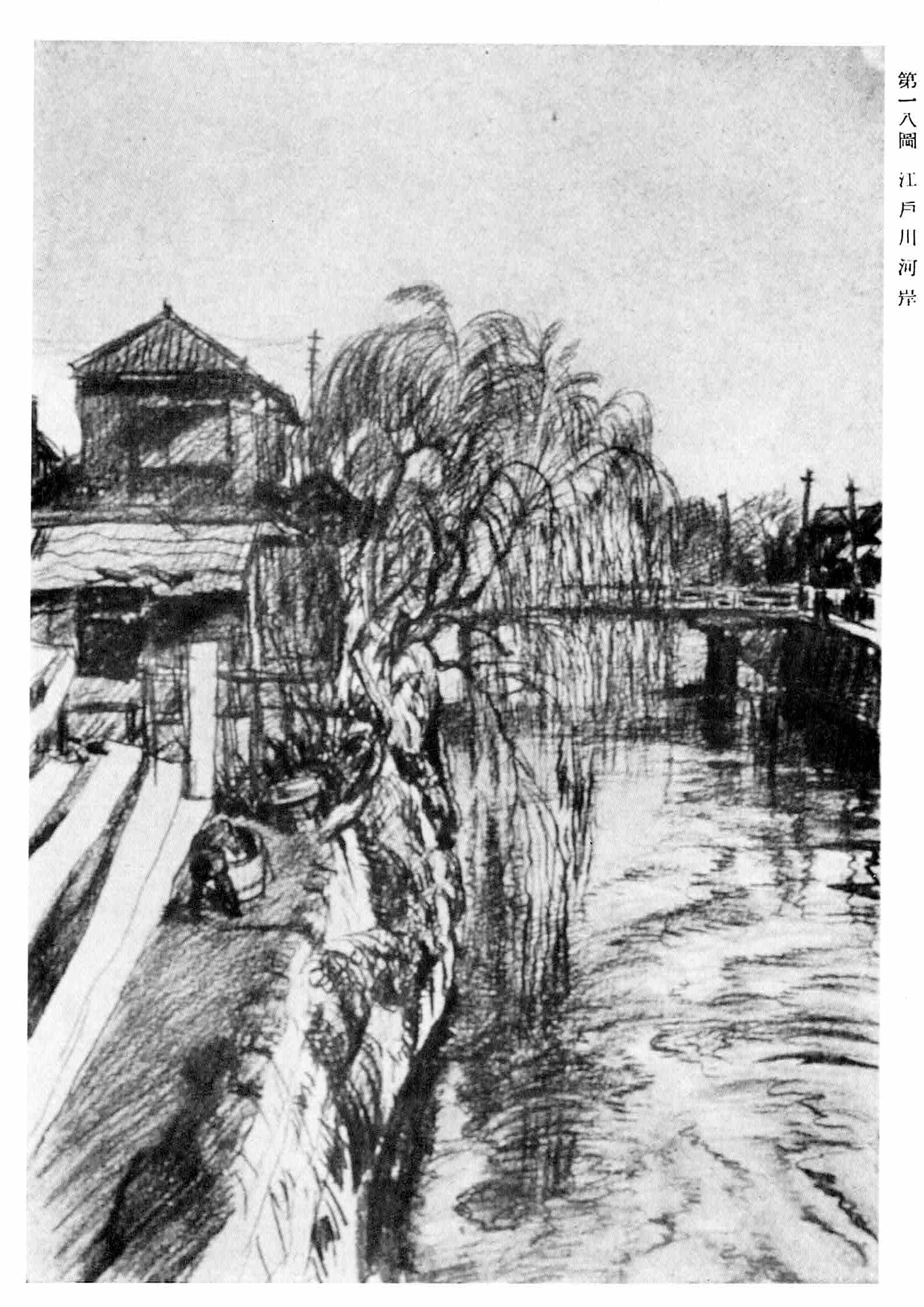

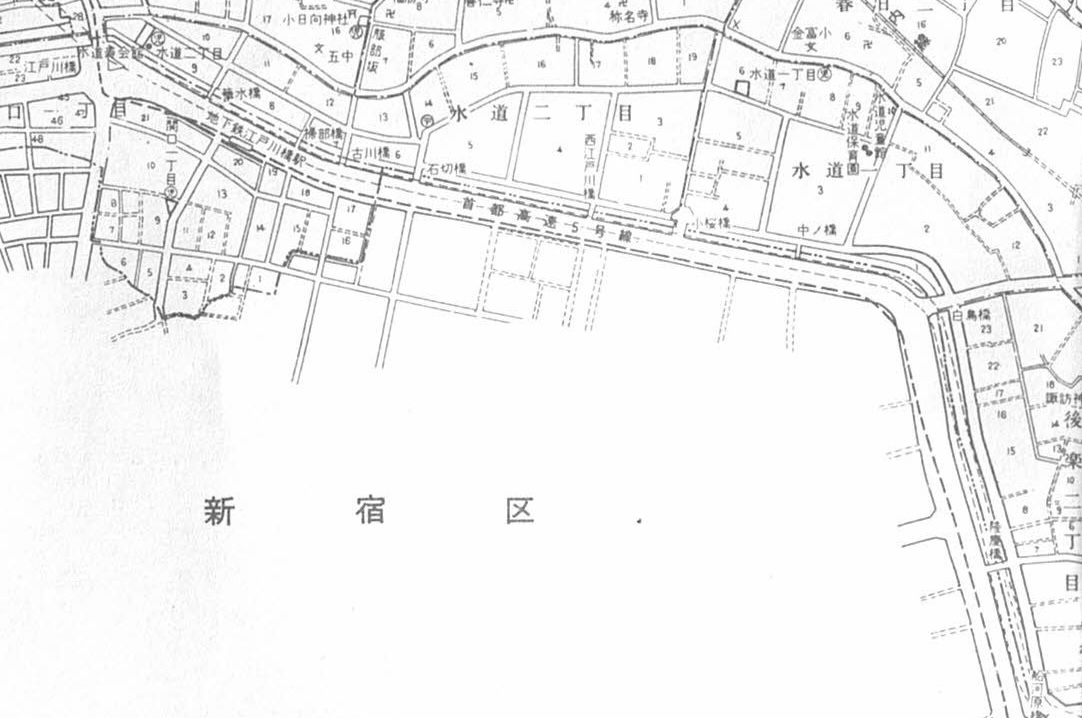

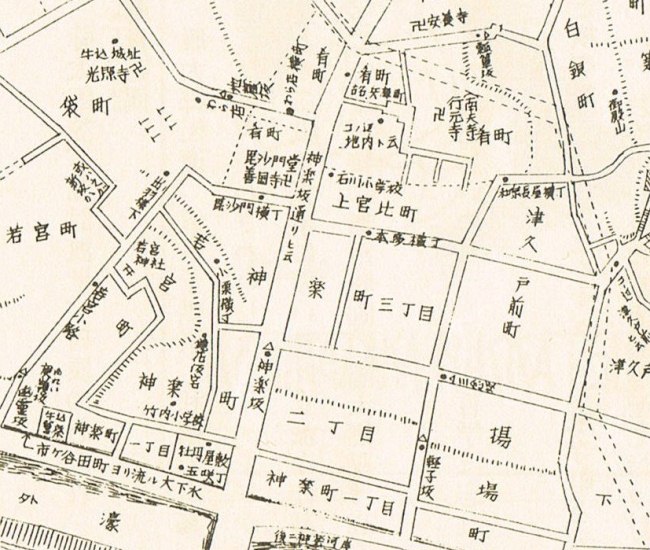

ここで、向島七福神の内訳を書いておきます。角田川七福神 (=隅田川七福神)牛込肴町になったことも あります。明治12年[1879]、復活が企画されましたが、これも失敗。また、明治末期、芝と亀戸の七福神が出ましたが、人気は出なかったといいます。

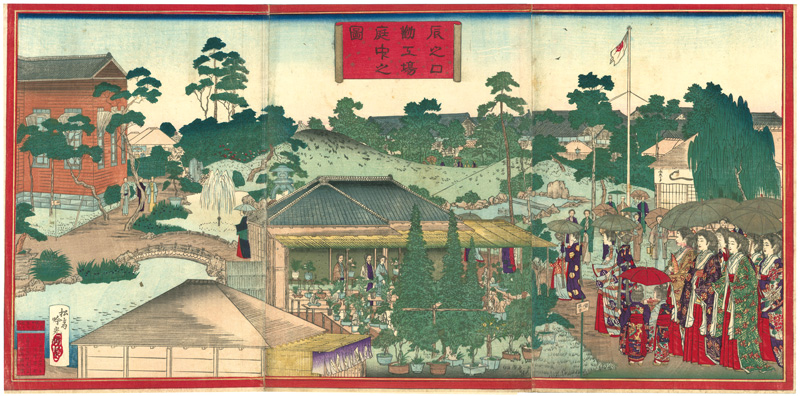

こうして、向島の七福は江戸人の春興として最早一つの常識とさえなるに至ったが、一方谷中の七福はどうなったかといえば、十方庵の「遊歴雑記」三編(文化13年[1816])には御府内七福神人方角詣として左の七ヶ所が挙げられている。横死 に起因しているものであって、この長距離(道程約三里)とこの組織では如何になんでも江戸人を吸収する事が出来ない。これでは急造の向島七福に圧倒されたのも無理からぬ事であり、谷中七福の声誉 はこうして徐々に転落の一途を辿るのみとなってしまったのは誠に余儀ない結果であった。所が、明治12年[1879]、不図した事から高畠藍泉 等の手により復活が企画され、山下の清凌亭 施版で橋本周延 画の道案内図が作られたり、清元仲太夫 、三遊亭金朝 等の鳴物入りもあって、ここに華々しく谷中七福は毎度のお目見得をする段取にまで漕ぎつけたのであった。但し、この時組織された七福の顔触れがまた変わっている。徴行 以来、漸く復活の曙光が見え出して来ている。尤も、同じ更生でもこの方は谷中と異り、鞠塢が組織したそのももの顔触れが揃って亳しも変動がなかった。現在、元旦より七日迄、七福の各社寺より尊像が授与される慣例は、この復活の機運が崩した小松宮殿下御徴行以来と云われ、大正12年[1923]の東京震災にも安政の轍を踏まず いよ/\増々盛大に行はれつつある現状に置かれている。北叟笑 まれても二の句 がないかも判らない。

横死 不慮の死。非業の死。天命を全うしないで死ぬこと

声誉 せいよ。よい評判。ほまれ。名声。

高畠藍泉 たかばたけらんせん。明治初期の戯作者と近代ジャーナリスト。

清凌亭 上野の料亭。「

佐多稲子の東京を歩く 」で詳しい

橋本周延 はしもと ちかのぶ。江戸城大奥の風俗画や明治開化期の婦人風俗画などの浮世絵師。

清元仲太夫 江戸浄瑠璃。江戸浄瑠璃とは江戸で成立か発達した浄瑠璃のこと。

三遊亭金朝 2代目でしょう。落語家。

徴行 びこう。身分の高い人などが身をやつしてひそかに出歩くこと。

北叟笑む ほくそえむ。うまくいったことに満足して、一人ひそかに笑う。

二の句 二の句が継げない。次に言う言葉が出てこない。あきれたり驚いたりして、次に言うべき言葉を失う。

小松宮殿下が徴行する明治33年[1900]からは、向島七福神が谷中七福などを打ち砕き、独占した形になりました。しかし、昭和7年[1932]には、新しい東海七福神が出現し、これで氾濫時代にはいりました。

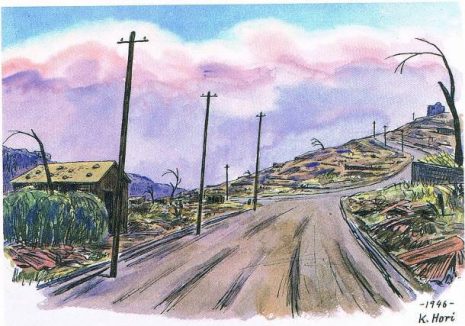

その七福氾濫時代のトップを切った東海七福の企画者はかくいう筆者であるが、生の動機は向島七福の創設当時と略 一致するもののあった事は断言し得られる。勿論これを企画した筆者は酒落でもなければ戯談 でもなく、まして御信心の押売りをしようなどと大それた考えは毛頭持ってなかった。それではどんな所に動機があったかといえば、沈滞しつつある品川を昔の繁栄に引戻そうとした一つの手段に過ぎなかったので、これを設置すればたとえ短時日の間でも他区民が同所へ足を踏み入れるであろうし、それと同時に煙草一ヶ位は売れるに違ひない、そうすれば品川という土地がどれだけ潤うであろうと考えたのが本当であった。

略 ほぼ。全部か完全にではないが、それに近い状態。

戯談 ぎだん。冗談。

昭和8年[1933]には麻布の稲荷七福が出てきます。

この東海七福の好評だった反響は直ちに昭和8年[1933]の麻布稲荷七福の創設によって現れて来ている。これは十番の末広稲荷の肝入りで、初めは麻布七福神として発表した所、七福が凡て対象のない稲荷を象った め、神社会から難じられ、已むを得ず稲荷の名を冠して麻布稲荷七福と看板を塗り代えたものであった。ここの宝船は皮付きの丸木舟で、尊像は悉く 木彫であるが、別に恵比寿に象っている恵比寿稲荷から鯛と宝珠 (いづれも土製)を吊した「女男登守 」というものが出されている。

象る かたどる。物の形を写し取る。ある形に似せて作る。

悉く ことごとく。全部。残らず。すべて。みな。

宝珠 ほうじゅ。宝石。

女男登守 「男女ともにお守りを授かる」という意味?

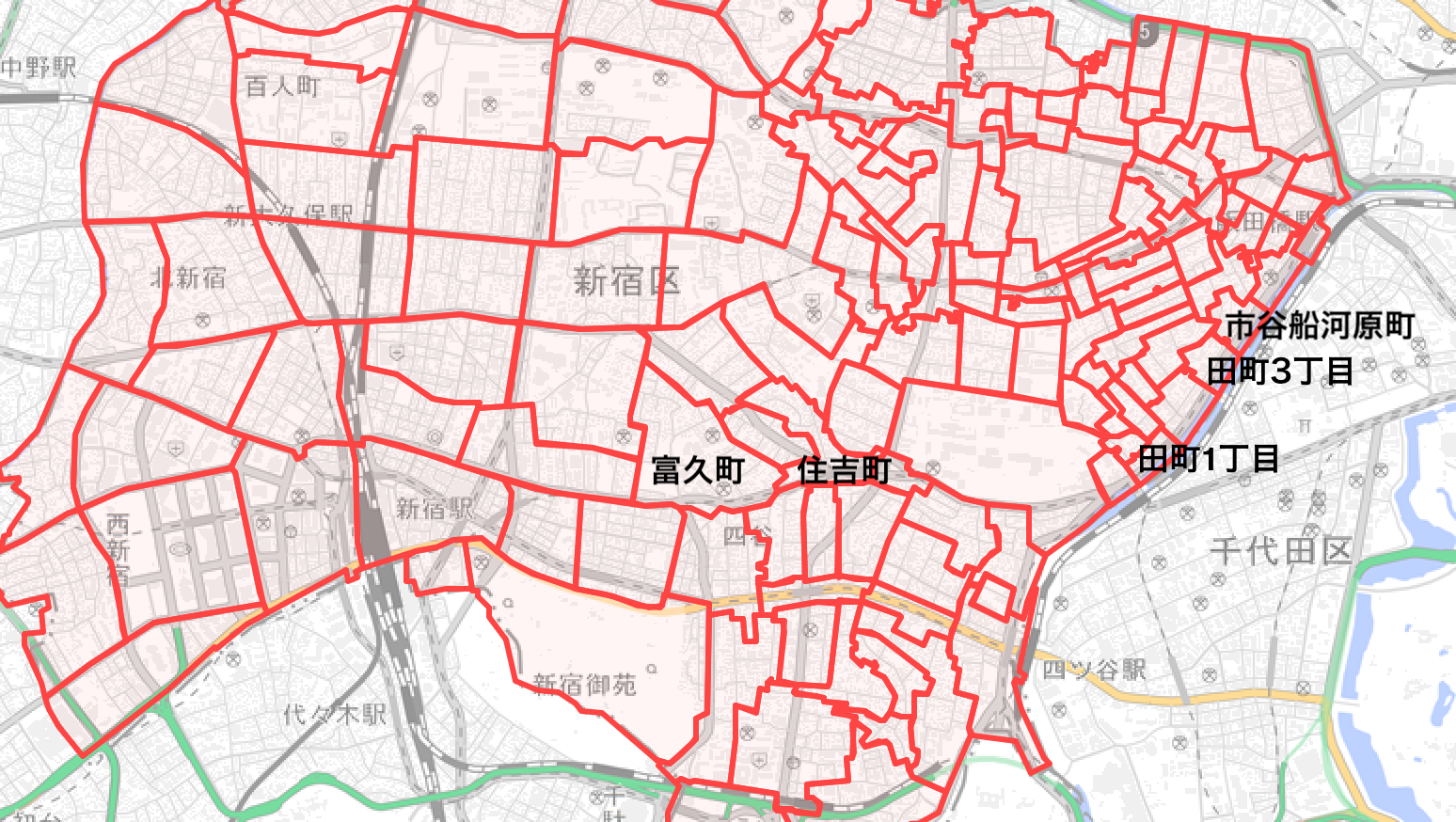

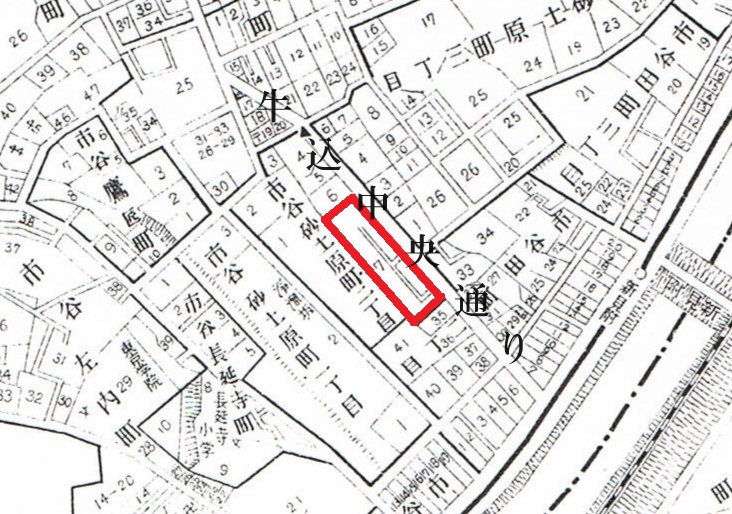

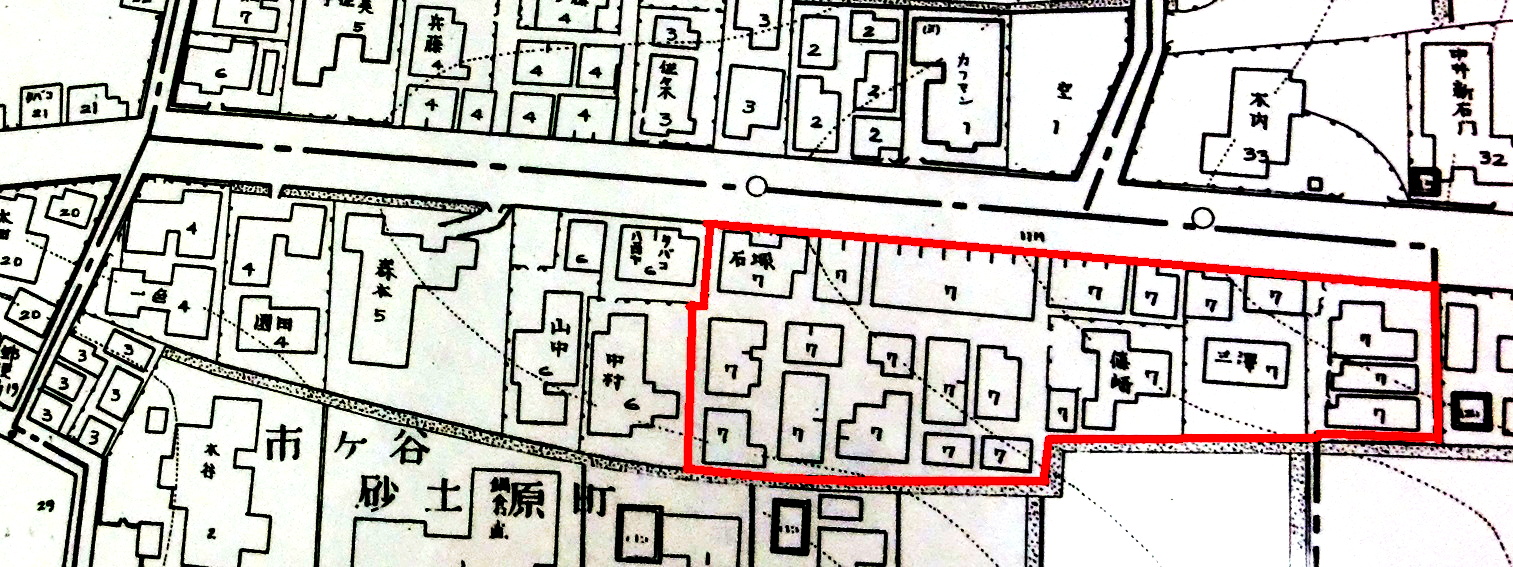

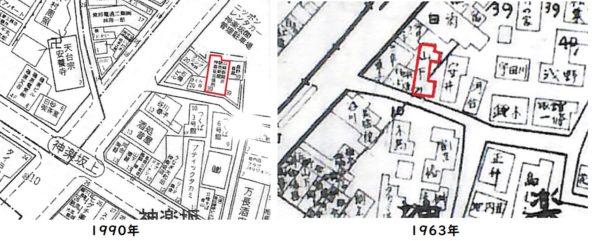

昭和9年[1934]、山の手七福神がついに登場し、柴又の七福神も開設されました。ここで、当時の山の手七福神を書いておきます。山の手七福神

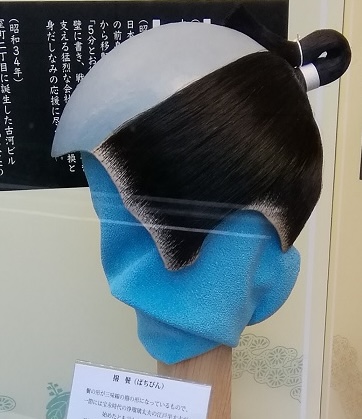

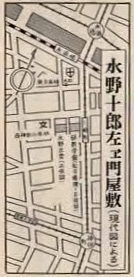

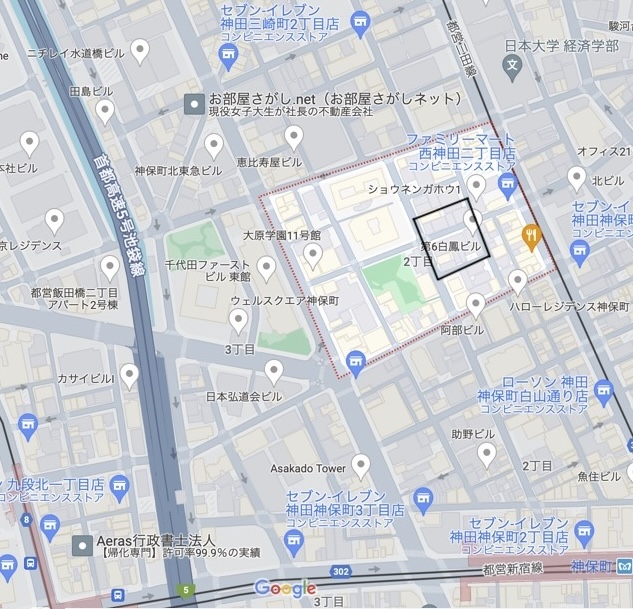

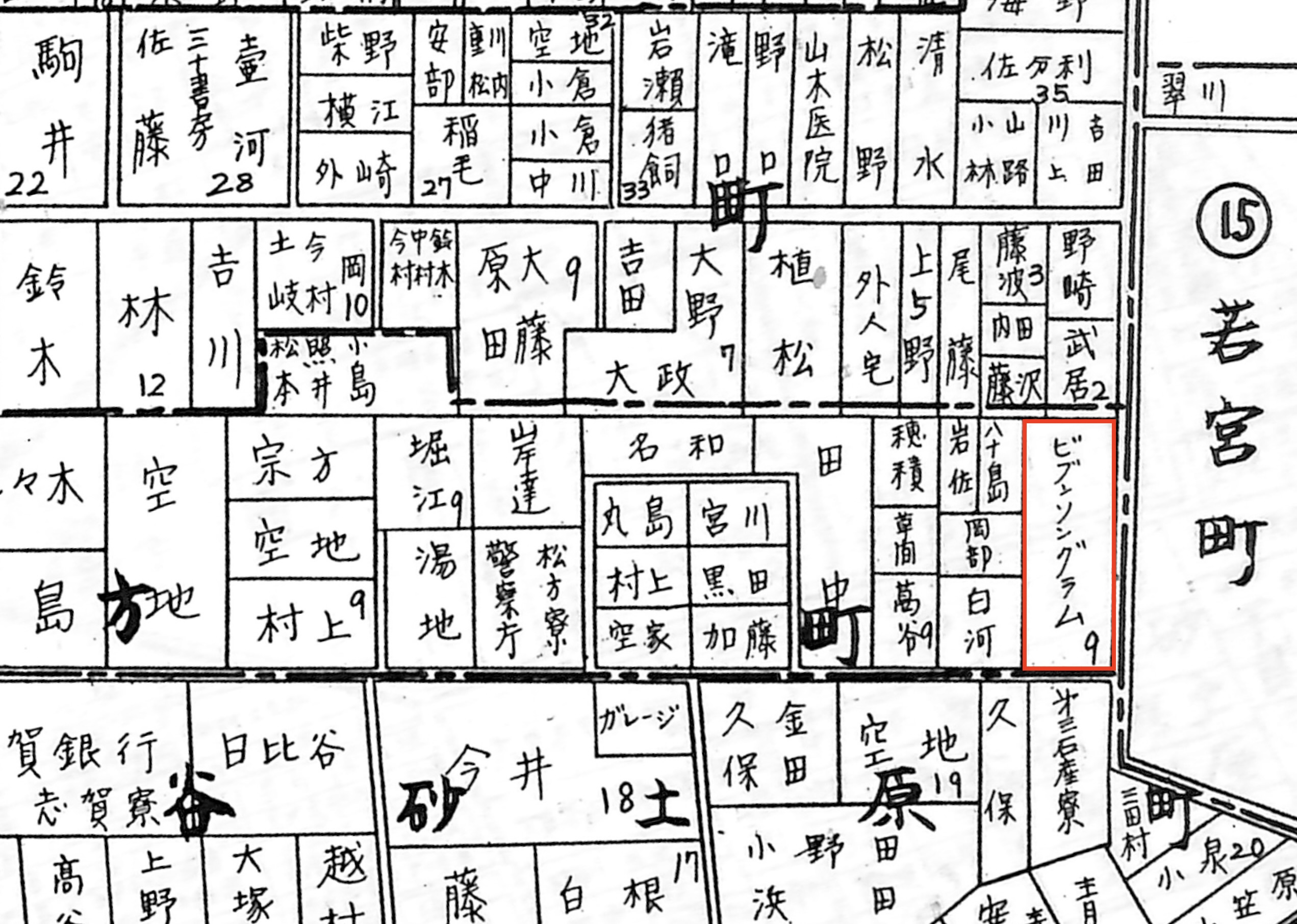

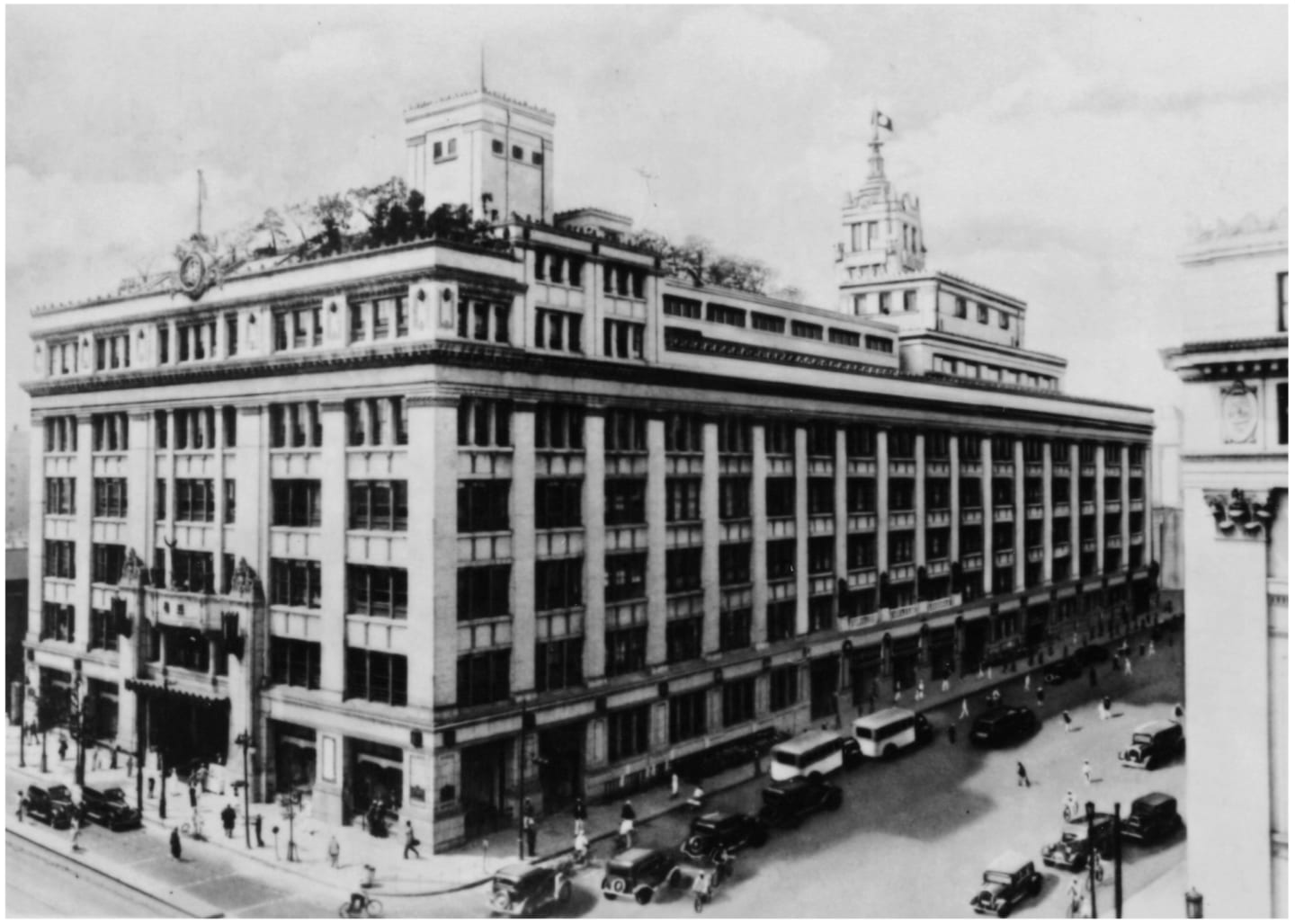

つづいて昭和9年[1934]、山之手七福と呼ぶものが出現した。これは大久保の中村花秀という俳人の発願であったが、花秀氏の依頼で筆者もこれに関し、最初から七福編成の難局に当たる光栄に浴せしめられた。当初候補に充てられた恵比寿の筑土八幡と布袋の新宿百貨店布袋屋中、筑戸八幡は氏子に反対されて途中から脱したので鬼王神社を以てこれに代え、布袋屋は営業の宣伝に供される恐れがある事と、元旦から三日間休業するため他との統一がとれぬ事とで排除し、太宗寺に交渉して更めて諾を得たものであった。ここの尊像は土製着彩、東海七福の類型であるが、宝船は経木 で製られた頗る瀟洒なものである。(尊像授期日、麻布、山之手共に例年元旦より七日迄)腰下げ が出されている。但し、柴又に限り例月7日に修行されるので、一年に通算すると 12日間腰下げが授与されるという事になる。

経木 きょうぎ。杉・檜などの木材を紙のように薄く削ったもの。

腰下げ 印籠いんろう ・タバコ入れ・

巾着きんちゃく などのように、腰にさげて携帯するもの。ミニチュア七福神よりも実用性は高いのでは?

「郷土玩具大成」の本は昭和10年(1935)に上梓した約90年昔の本です。七福神が競争する、結構本気で真剣な張り合いでした。しかも、筆者自身が「東海七福神」や「山の手七福神」でダイレクトに出ている。山の手七福神ははるか昔から決めたものではなく、昭和9年に決まったものでした。

5丁目

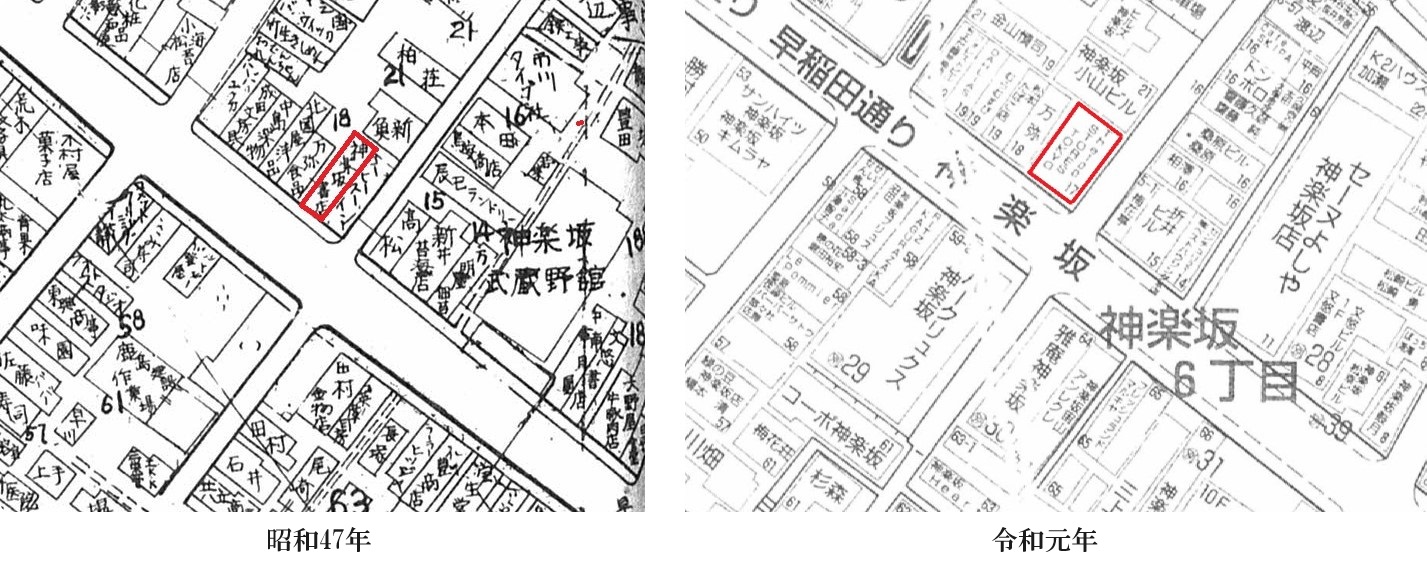

善國寺